Pianos, Priests, and Popular Culture

/

231

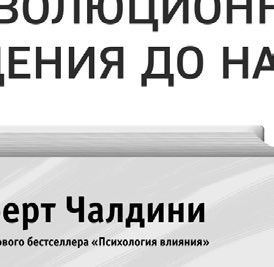

demands to render style consumable. ”50 Seen against the backdrop of industry dictates and other extratextual protocols, Sirk’s melodramas of the 1950s—like To New Shores— catered directly to the audience’s fantasies of consumption. Sirk’s allegedly dissident style, according to this newer generation of critics, provided images of plentitude for a bourgeois society deeply submerged in hegemonic ideologies of domesticity and affluence.51

What is important to note in closing is that Sirk’s American work after The First Legion continually replays as pastiche the earlier film’s juxtaposition of high and low. Whatever their actual effects on historical spectators, even Sirk’s most extravagant pageants made at Universal invoke his 1950

critique of aesthetic instrumentalization and commodification. In often paradoxical and self-contradictory ways Sirk’s aesthetic resistance and cultural elitism thus became the stuff of popular entertainment itself. Nowhere does this become more evident than in Sirk’s penultimate Hollywood film, A Time to Love and a Time to Die (1957). In one particular sequence Sirk leads the viewer into the villa of the Nazi official Oscar Binding. We see the villa’s walls cluttered with confiscated artworks that are arranged like trophies. While a concentration camp officer plays Beethoven on the piano in the posture of a nineteenth-century genius artist, we view Binding and some prostitutes indulging in animalistic desires (fig. 28). In another important sequence, opposed to this scenario of aesthetic instrumentalization and coordination, we follow the protagonist, Ernst Graeber, as he wanders through the rubble of his hometown. Suddenly, his attention is drawn to the grotesque sound of atonal music, produced by a wire scraping over the strings of a broken piano. Heard against the decadent uses of Beethoven, the piano’s dissonant, unauthored chords emerge as an idiom of authentic, noninstrumental articulation. They intone a language of suffering and negativity, a cryptogram of despair whose puzzling modernity lies in its mimetic relation to a world of material desolation. Authentic art not only has become literally homeless, but it also must eliminate the organizing power of the artist, the bourgeois genius so popular in the iconography of twentieth-century mass culture. As a mimesis of destruction, art challenges in this sequence the attempt to unify high and low in spectacles of false reconciliation. No longer defined as a work, it punctures the reshaping of modern culture as religion and cult of standardization. In their very negativity and dissonance, the piano’s enigmatic sounds thus encrypt the utopian idea of aesthetic experience as a yielding to and becoming other.

They recapture a sense of spontaneity that points beyond the scenes of cultural reification. Forsaking all magic, Sirk in this chilling sequence actualizes magic and plays it out against the sorcery of cultural leveling. He en-

07-C2205 8/17/02 3:39 PM Page 232

232

/

Berlin in Hollywood, 1939 –1955

Figure 28. Art, music, and Nazi perversion: Douglas Sirk’s A Time to Love and a Time to Die (1958). Courtesy of Filmmuseum Berlin—Deutsche Kinemathek.

dorses a form of aesthetic experience and autonomy that, in Adorno’s words, “renounces happiness for the sake of happiness, thus enabling desire to survive in art.”52

Similar to many West German films shot during the Adenauer era, A Time to Love and a Time to Die presents Nazi warfare as a fiasco of operatic dimensions. It recasts the past as fate and natural disaster and suggests that modern art has no choice but to bear the scars of havoc and disruption. Art’s esoteric task is to express the impossibility of expression. Its truth and authenticity lies in articulating that authentic experience has become untenable. For Sirk, as much as for Adorno, the role of modern art is thus that of a camera obscura belaboring the fact that nothing concerning art goes without saying anymore, including its own right to exist. Genuine art reflects the desolate landscapes of modern life, yet it does so only through acts of self-conscious negation, by radically separating itself from being and the logic of industrial culture. It is the remaining paradox, challenge, and scandal of Sirk’s American work that it sought to examine these propositions with the

07-C2205 8/17/02 3:39 PM Page 233

Pianos, Priests, and Popular Culture

/

233

means of industrial culture itself, that it aspired to amalgamate populist and antipopulist stances and elevate mass culture to a laboratory of aesthetic reflection. Sirk’s later popularity among academics and filmmakers, in turn, resulted in no small measure from the extent to which Sirk himself—unlike Lang or Siodmak an ardent reader of contemporary film scholarship—was able and eager to couch such ambitions in sophisticated theoretical formulas. In many strange ways, indeed, Sirk’s frequent self-interpretations not only provided film scholars of later periods with an opportune political aura, but they also distracted from the fact that the deconstructivist theory of textual resistance, in its zealous search for instances of subversion in mass culture, excised any further examination of the popular’s historically specific institutions and practices of consumption.

08-C2205 8/17/02 3:39 PM Page 234

8 Isolde Resurrected

Curtis Bernhardt’s Interrupted

Melody

Douglas Sirk’s The First Legion pictured the American postwar period in terms of a melodramatic struggle between legitimate art and standardized consumption. Sirk understood modern culture as a Manichean confrontation between the incompatible codes of aesthetic experimentation and commodified diversion, even though the point might rather be to demonstrate that their “much heralded mutual exclusiveness is really a sign of their secret interdependence.”1 Sirk’s praise of authentic art thus critically elided the fact that neither mass culture nor aesthetic modernism can do without the other, that one owes its emergence and continued existence to the other.

Driven by his hope for noncommodified authenticity, Sirk’s denigration of Fordist mass culture not only reinforced conventional binaries between high/low, true/false, and active/passive, but it also proved to be strangely out of synch with the historical developments of American society during the 1950s. For however one conceptualizes the location of industrial mass culture and its relation to legitimate art, it is difficult not to agree that 1950s American consumer capitalism ended up displacing many of the institutions, meanings, and modes of consumption that had structured the U.S.

leisure market during previous decades. Often, and understandably, scolded as a period of suburban withdrawal and dull conservatism, the 1950s increasingly consumed the very categories according to which Sirk hoped to reform postwar culture.

A 1955 article in Fortune summarized this transformation: “The sharp-est fact about the postwar leisure market is the growing preference for active fun rather than mere onlooking.”2 The 1950s saw the emergence of a new affluent middle class that did not hesitate to pursue traditional elite activities with a middle-class kind of zeal. The egalitarian populism of the 234

08-C2205 8/17/02 3:39 PM Page 235

Isolde Resurrected

/

235

Depression era thus gave way, on the one hand, to a conception of culture as a sign of social differentiation and, on the other, to a redefinition of amuse-ment as participatory event. Television now serviced what had drawn previous mass audiences to movie theaters, and America’s new middle class demanded different and more diversified products from the film industry.

“As the composition of the moviegoing audience shifted from an ill-defined and somewhat amorphous general audience to a more highly stratified, younger, better-educated, and more affluent middle-class audience,”3 the motion picture industry developed new generic formulas that would cross former distinctions between elite and popular culture and thus liquefy some of the essential boundaries that had structured the era of the classical studio system.

The breakthrough of television after 1948 has often been seen as the primary cause for the decline of the studio system during the 1950s and for Hollywood’s redemptive introduction of widescreen exhibition formats. Inaugurated in the early 1950s in various competing versions (Cinerama, CinemaScope, VistaVision, Todd-AO, Panavision), widescreen cinema, according to this argument, capitalized on what television was unable to grant. It was meant to lure people away from the minute images of early television sets by offering visual grandeur and exaltation. But to understand the advent of new exhibition standards during the early 1950s as merely an antidote to television clearly underestimates the extent to which widescreen cinema was both symptom and agent of larger cultural transformations. Unlike earlier attempts to establish wide-film formats during the 1920s, the widescreen revolution succeeded in the 1950s because American society was ready for it. Widescreen cinema, in other words, was not merely a result of the industry’s endeavor to outshine television; rather, it actively participated in a remarkable diversification of American leisure-time activities, a crucial transformation of dominant paradigms of spectatorship, and a—however ideological—redefinition of mass consumption as participatory event.

Fredric Jameson has argued that every modern social formation must be viewed as a site at which nonsynchronous developments and temporal overlays are the order of the day.4 Each historical moment and its forms of textualization, according to Jameson, are marked by older methods of production, but they will simultaneously articulate anticipatory practices and discourses. Jameson’s theory of nonsynchronicity, I submit, elucidates the curious location of widescreen filmmaking in the 1950s in at least three respects. First, CinemaScope may have reemphasized the exhibitionist aspects

08-C2205 8/17/02 3:39 PM Page 236

236

/

Berlin in Hollywood, 1939 –1955