C H A P T E R T W O

soon the three powers became involved in the Great Game over who would control Inner Asia.

Rulers of China and Russia subdued the princes in Mongol-Tibetan countries and turned them into their vassals, leaving Buddhist clergy alone. Frequently, Buddhist monks were pitted against secular princes, who were treated as potential rebels. In the 1600s and 1700s, Tibetan Buddhism began to l ourish, and lamas were free to conduct missionary work. As a result, by the end of the eighteenth century the “yellow faith”

had spread all over Mongolia and made successful inroads in southern Siberia. h e privileged status of the Buddhist teaching, which eventually crippled secular power, might explain why later monasteries and monks usually headed social and political movements in the Tibetan-Mongol world. It also explains why, in modern times, at i rst Tibet and then Mongolia became theocracies (states headed by clergy).

Tibet was ruled by the Dalai Lama (“Ocean of Wisdom” in Tibetan), the chief religious leader and administrator. Yet he did not enjoy total power. h e Panchen Lama, abbot of the Tashilumpho monastery, traditionally exercised control over the eastern part of the country. Panchen Lamas, whom many viewed as the spiritual leaders of Tibet, did not pay taxes and even had small armies. h is special status originated from the seventeenth century, when Lobzang Gyaltsen, abbot of the Tashilumpho monastery, spiritually guided the i t h Dalai Lama (1617–82), the great reformer who built up Tibet. As a gesture of deep gratitude to his spiritual teacher, the Lhasa ruler endowed the abbot with the title of Panchen Lama, “Great Scholar,” and granted Tashilumpho a special tax-exempt status. In modern times, this privileged status of the Panchen Lamas became a liability, undermining and chipping away Tibetan unity and sovereignty, to the joy of its close neighbors, some of whom did not miss any chance to pit the Ocean of Wisdom against the Great Scholar.

h eologically speaking, Panchens stood even higher than Dalai Lamas. Tashilumpho abbots were considered the reincarnation of Buddha Amitabha (one of the i ve top Buddhas, in addition to Gautama), 20

P O W E R F O R T H E P O W E R L E S S

whereas Dalais were only reincarnations of Avalokitesvara, who was only a bodhisattva and the manifestation of Buddha Amitabha. 1 Besides, the faithful linked Panchens to the Shambhala prophecy; at the end of the eighteenth century one of the Tashilumpho abbots composed a guidebook to this great northern land of spiritual bliss and plenty, 2

and many monks came to believe that in the future the Great Scholar would be reborn as a Shambhala king to deliver people from existing miseries. Despite such impeccable religious credentials, real power in Tibet belonged to the Dalai Lama.

In Mongolia, traditionally much power was concentrated in the hands of the Bogdo-gegen (Great Holy One). h is third most prominent man in the Tibetan Buddhist hierarchy, at er the Dalai and the Panchen, was considered the reincarnation of the famous Tibetan scholar Taranatha, who had lived in the 1500s. At i rst, Bogdo reincarnations were found among Mongol princely families, but, haunted by the specter of Mongol separatism, the Manchu emperors curtailed this practice and ordered that all new Bogdo come only from Tibet. 3 At er the country freed itself from the Chinese in 1912, the Great Holy One was elevated to the head of the state and, just like Tibet, Mongolia became a theocracy.

Tibetan Buddhist countries were mostly populated by nomads who raised horses and sheep. About 30 percent of the entire male population were lamas. Tibet was the only country that, besides the nomads, had large groups of peasants and crat smen. As parts of the Chinese Empire, Mongolia, Tibet, and Tuva, as well as the Kalmyk, Buryat, and Altaians within the Russian Empire enjoyed considerable self-rule. As long as they recognized themselves as subjects of their empires and agreed to perform a few services (usually protecting the frontiers and paying tribute), they were let alone. Moreover, in China, the Manchu Dynasty, following the old tactics of divide and rule, went further, segregating Tibetan Buddhist people from the rest of the populations. Mongols and Tibetans were not allowed to mingle with the Chinese, wear their clothing, or learn their language. At the same time, Chinese peasants were forbidden to settle in Tibet and Mongolia.

21

C H A P T E R T W O

At the end of the nineteenth century everything changed. Famine and population pressure in China put an end to no-settlement policies.

While mountainous Tibet was of little interest, the pasturelands of the Mongols looked very appealing, and the Manchu began to squeeze them from their native habitats and curtail their traditional law. By the beginning of the twentieth century, southern (Inner) Mongolia was l ooded with Chinese, and in all major cities of the northern (Outer) part of the country, Mongol oi cials were replaced with Chinese mandarins.

Simultaneously, between the 1880s and 1910s, at er serfdom in Russia was terminated, hundreds of thousands of settlers l ocked to southern Siberia in search of good pasture and plow lands. Although Siberia was large enough to absorb many of these newcomers, in the Altai and the Trans-Baikal, the most lucrative settlement areas, Russian newcomers began to clash with local nomads over land. Between 1896 and 1916, to speed up colonization and link the eastern borderlands to the rest of the country, the Russian government built the Trans-Siberian railroad.

To the dismay of indigenous folk, the Russian Empire, like its Manchu counterpart, cracked down on their traditional self-rule and law. Jealous of Russian advances and fearful that the Russians would roll southward into Mongolia and on to the Far East, the Chinese doubled their colonization moves, expanding to Manchuria and further into Inner Mongolia, where the number of Mongols soon shrank to 33 percent.

Replicating Russian steps in Siberia, in 1906 the Chinese government built a railroad to Inner Mongolia, drawing this borderland area closer to Beijing. h e centuries-old policy of noninterference was shredded.

From then on there would be no peace between the Mongols and the Chinese. As one historian of the period wrote, the entire Mongol history in the i rst half of the twentieth century became saturated with anti-Chinese sentiments. 4

Although the rugged terrain of Tibet did not attract the hordes of settlers and it was fortunate to avoid the fate of Mongolia, the Forbidden Kingdom was not immune to anti-Chinese sentiments. Tibetans equally distrusted the Manchu Empire, which wrecked their sovereignty in 1908

22

P O W E R F O R T H E P O W E R L E S S

by bringing a detachment of troops to Lhasa, stripping the Dalai Lama of his power, and giving decision-making authority to two governmental inspectors (ambans) sent from Beijing. Besides, in eastern Tibet, the Manchus kicked out all local administrators and replaced them with Chinese bureaucrats. Although these measures were a response to the 1904 military strike at Tibet by the English, the Forbidden Kingdom recognized them as an attack on its sovereignty.

Anti-Chinese Prophecies in Tibet and Mongolia Resorting to prophecies such as Shambhala was one way for Tibetans and Mongols to empower themselves to deal with the Chinese advances.

As early as the 1840s the French missionary Abbé Huc, who visited the Tashilumpho monastery, described how this particular myth served as a spiritual resistance against China’s infringement on Tibetan sovereignty.

h e version of the prophecy that he heard said that when the Buddhist faith declined, the Chinese would take over the Forbidden Kingdom.

h e only place where the true faith would survive would be the Kalon (Kalachakra?) fellowship, a sacred brotherhood of the Panchen Lama’s devoted followers, who would i nd refuge in the north somewhere between the Altai and Tuva. In this mysterious faraway northern country, a new reincarnation of the Panchen Lama would be found.

In the meantime, the subjugated people would rise up against the invaders in a spontaneous rebellion: “h e h ibetans will take up arms, and will massacre in one day all the Chinese, young and old, and not one of them shall trespass the frontiers.” At er this, the infuriated Manchu emperor would gather a huge army and storm into Tibet, slashing and burning: “Blood will l ow in torrents, the streams will be red with gore, and the Chinese will gain possession of h ibet.” h at was when the reincarnated Panchen Lama, the “saint of all saints,” would step in to free the faithful from the ini dels. h e spiritual leader of Tibet would assemble the members of his sacred society, both alive and dead, into a powerful army equipped with arrows and fusils. Headed 23

C H A P T E R T W O

by the Panchen, the holy army would march southward and cut the Chinese into pieces. Not only would he wipe out the enemies of the faith, but he would also take over Tibet, Mongolia, all of China, and even the faraway great state of Oros (Russia). h e Panchen Lama would

eventually be proclaimed the universal ruler, and the Tibetan Buddhist faith would triumph all over the world: “Superb Lamaseries would rise everywhere and the whole world will recognize an ini nite power of Buddhic prayers.” 5

h e world of Inner Asian nomads was saturated with epic legends, myths, fairy tales, and stories, which common folk, mostly illiterate shepherds, shared with each other or received from storytellers and oracles. Prophecies were an important part of this oral culture, helping the populace deal with the uncertainties of life and mentally digest dramatic changes in times of troubles. 6 Spreading like wildi re over plains and deserts, prophecies comforted people, mobilized them against enemies, and guided them to the correct path. Not infrequently, learned lamas put these messages down on paper and passed them around as chain letters to other monasteries.

In the Mongol-Tibetan world people took these prophecies very seriously. For example, Abbé Huc was stunned by how passionately Tibetans believed in the reality of the Shambhala prophecy, taking for granted not only its general message but also its particular details of what was about to happen: “Everyone speaks of them as of things certain and in-fallible.” Although loaded with Christian biases, the perceptive missionary also noted the explosive power of this lingering prophecy: “h ese absurd and extravagant ideas have made their way with the masses, and particularly with those who belong to the society of the Kalons, that they are very likely, at some future day, to cause a revolution in h ibet.” 7 As if anticipating actual events that would take place in Inner Asia in the early twentieth century, the holy father correctly predicted that it would take only one smart and strong-willed individual to come from the north and proclaim himself the Panchen Lama in order to ride these popular sentiments.

24

P O W E R F O R T H E P O W E R L E S S

Besides Shambhala, people of the Mongol-Tibetan world shared other tools of spiritual resistance. One of them was turning epic heroes and actual historical characters into sacred beings. For example, the famous Genghis Khan became a god-protector of Mongol Buddhism.

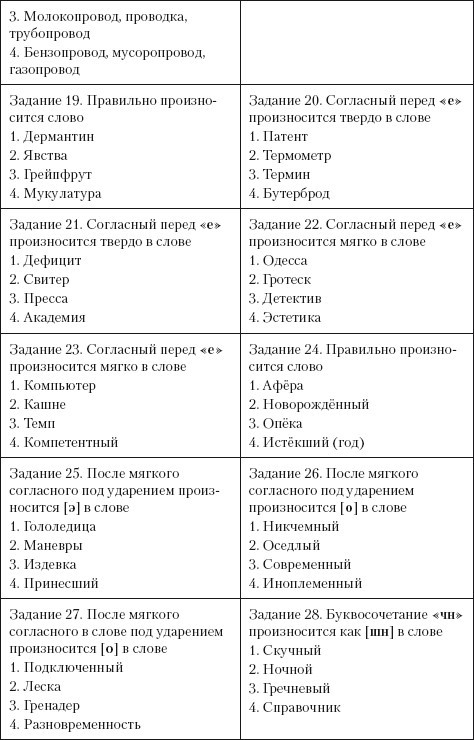

Another popular deity was Geser Khan, a legendary hero immortalized in epic tales widespread among the Buryat, eastern Mongols, and Tibetans. Sent by the god Hormusta to free people from evil, Geser Figure 2.1. Geser the Lion, an epic hero-liberator in Mongol-Tibetan folklore.

25