‘I’m not sure. About five hundred, give or take a few.’

‘And the King?’

‘He’s well enough. He was a wee bit upset when we banged his door in and he still canna understand it how the sixty men he had with him in the house managed to drive off two hundred Borderers. He thinks it was God saved him, though Chancellor Melville did his best when ye sent him word.’

‘Is that all, a wee bit upset?’

‘Well, he’s verra upset, to tell ye the truth. I hear he’s on his way to Jedburgh with three thousand men to do some justice.’

‘And Bothwell?’

‘Gone north to the Highlands. He’s worn out his welcome here and he knows it.’

They looked at each other in silence for a moment, Carey wondering if he dared ask.

‘Ay,’ said Jock, ‘I dinna like his way of doing things. About Sweetmilk.’

‘Yes.’

‘I know who killed him.’

‘Oh?’ said Carey carefully. ‘Did... er... did Mary tell you?’

Jock spat. ‘Not a peep out of her and I broke a stick thrashing her.’

‘Then how do you know?’

Jock stared off into the distance, one hand on the bough beside him.

‘All the time we were conversing on top of Netherby tower there was something about your face that was troubling me, Courtier. I didna mind me what it was until we’d let ye go and then it came to me. It was the cut on your cheek.’

Carey had forgotten all about it, though he put his finger to the scar now. ‘What about it?’

‘I spent a full night before he was buried, looking at my Sweetmilk’s poor dead face,’ said Jock, ‘and it was sorrowful what the crows had done to it, but none of the peckmarks had bled. Except one, the one on his cheek, like yours, that had bled, ay and clotted too. It was the same shape, ye mind, like a star, made by a fancy ring.’

Jock’s mouth worked. ‘I asked the Earl if anyone hit ye while ye were at Netherby playing at pedlars. He said it was Jock Hepburn that struck you for not calling him sir. Nobody else until I got to work on ye. And Hepburn had a ring like a star, with emeralds on it.’

‘Had?’ asked Carey, feeling hollow and tired.

‘Ay, had,’ said Jock, ‘I asked him, he admitted he hit Sweetmilk, he admitted Sweetmilk called him out. He denied shooting my son in the back, but he lied.’

‘Did he have a trial?’ demanded Carey, his voice shaking with a sudden surprising rage. ‘Did he get a chance at justice?’

‘Justice? There ye go again, Courtier, you’re ower impractical. What justice did he give my Sweetmilk? If he’d killed him honourably in a duel, ay well, it would have been sorrowful, but what he did... He’s had all the justice he deserves.’

It was on the tip of Carey’s tongue to tell Jock the truth about his daughter, but somehow the words stuck there. The silence broken by horse noises was all around him while he tried to decide: would justice truly be served by her hanging? Would Jock even believe him? Mary’s death would bring back neither Sweetmilk nor Hepburn. Perhaps Elizabeth was right; he remembered her anger, which had puzzled him. At last he said, ‘Where is Hepburn now?’

‘His soul’s in hell, but ye’ll find his body where he left Sweetmilk’s, if you’ve a mind to go fetch it. I wouldnae bother, myself. It’s no’ very pretty, ye follow.’

‘You could have waited, Jock,’ said Carey tightly, ‘I was planning to arrest the murderer. You could have waited for a trial and proper justice.’

Jock shrugged. ‘Why?’ he asked. ‘Ye’re begrudging an old man healing his heart? Besides Hepburn could likely buy his way clear—who cares about the killing of a reiver? This way Sweetmilk can rest quiet.’

‘Very neat,’ said Carey bitterly.

He turned his horse away to return to Dodd and start the long wearisome job of rounding up the horses, sorting them out by brand and knowledge, and take them back to their rightful owners. Jock called after him, ‘I’m in debt to ye, Courtier. I’ll mind ye if we meet in a fight and if ye need aid from the Grahams, ye’ve only to call on me.’

Carey turned back.

‘God forbid,’ he said, ‘that I should ever need help from the likes of you.’

Jock was not offended. ‘Ay, perhaps He will. But if He doesna, my offer stands. Good day to ye, Courtier.’

A Season of Knives

To Melanie, with many thanks

Foreword

P.F. CHISHOLM WRITES YOU-ARE-THERE! BOOKS.

A You-Are-THERE! book is a book that can make you feel the nap of Sir Robert Carey’s black velvet doublet beneath your fingertips. A You-Are-THERE! book can make you smell the sewer in the streets of Elizabethan Carlisle. A You-Are-THERE! book can make you taste the ale at Bessie Storey’s alehouse outside the Captain’s Gate at Berwick garrison, and a You-Are-THERE! book can make you hear the arquebuses firing at Netherby tower. A You-Are-THERE! book can make you feel like you’re ready to pack up and move THERE, if only you had a time machine.

THERE, in the case of P.F. Chisholm, is the nebulous and ever-changing border between Scotland and England in 1592, the thirty-fourth year of the reign of Good Queen Bess, five years after the Spanish Armada, fifty-one years after Henry VIII beheaded his last queen. Reivers with a high disregard for the allegiance or for that matter, the nationality of their victims roved freely back and forth across this border during this time, pillaging, plundering, assaulting and killing as they went.

Into this scene of mayhem and murder gallops Sir Robert Carey, the central figure of the mystery novels by P.F. Chisholm.

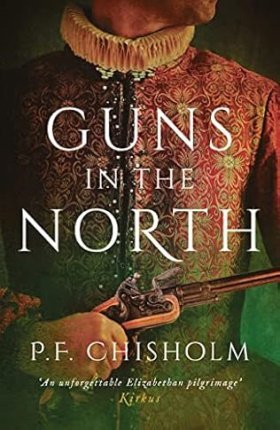

Sir Robert is the Deputy Warden of the West March, and his duty is to enforce the peace on the Border. Since everyone on the English side is first cousin once removed to everyone on the Scottish side, it is frequently difficult to tell his men which way to shoot. The first in the series, A Famine of Horses, begins with Sir Robert’s first day on the job and the murder of Sweetmilk Geordie Graham. In A Season of Knives Sir Robert is framed and tried for the murder of paymaster Jemmy Atkinson. On night patrol in A Surfeit of Guns, he uncovers a plot to smuggle arms across the Border.