“How do you mean?”

“Herbert was a homosexual.” She enunciated the word with a kind of clinical accuracy. “He wouldn’t come out. But everyone around him knew it. Certainly I knew it, and I did everything I could to make him understand it didn’t matter. But, after a lifetime of hiding in his own skin, he lost his baby girl and his heart couldn’t take it. My husband quite literally died of heart failure.”

“And you? How have you managed to survive?”

“I found strengths I never knew I had. And I come here—to spend time with her spirit. We…communicate. I know that sounds a bit odd but it’s true.”

Mrs. Persky pushed a chair away from the rolltop desk and dragged out a medium-sized scratched-up red trunk. I caught a glimpse out the window: the backyard was green, pastoral, the pool slim and clean, but that’s where the papers said the dirty deed went down. Murder by bludgeoning. She took a blue ceramic pitcher off the desk, shook out a key, and opened the trunk.

“I certainly hope you aren’t expecting to solve any crimes,” she said. “Emil paid the price for what he did. And if there was anything here that constituted a clue, the police would have found it years ago.”

“Police can make mistakes,” I said feebly.

She ignored the remark. “Did Charles tell you that my husband engaged lawyers to help Emil when he got arrested?”

“He didn’t mention that.”

“Of course not, why would he? They accomplished nothing—they never got a chance. But, okay. If Charles thinks he has the courage to rip open the old wounds, more power to him.”

I almost mentioned Hawley’s visit—then I thought better of it. “I guess Mr. Elkaim wants to give it one last try—you know, to prove his son’s innocence.”

“He’s punishing himself,” she said. “It’s the punishment he really craves.”

I knelt to the trunk and tried to stave off disappointment—there wasn’t much. Ten or twelve LPs. Iron Butterfly, Something New by the Beatles, the soundtrack to Mary Poppins. A little lime-green Easy-Bake Oven with the metal part rusted over. A stuffed gray rabbit with blue button eyes. A folded faded pink taffeta dress, a pair of little girl’s black patent leather tap shoes, and a pair of cream leather gloves that used to be white—the little leather bluebirds sewn into the palms were losing their stitching. There were also three super-old copies of Teen Magazine, all midsixties. The articles they promised on the covers had the afterglow of dark premonition: “Demon Eyes—For the Devilish You”; “Root of It All—Hair Color Hints”; “Promises Promises”; “Keeping Secrets”; and “Report from Death Row: A Condemned Man Reflects on His Teen Years.” There was also a copy of a rock magazine called Flipside from 1981 or 1982 with some kids holding a picture of Manson on the cover, and tucked inside the mag was a flyer for Mod Night at the Bullet Club. The address was Argyle, off Hollywood Boulevard. A band called The Unknowns was going to play; tickets were three dollars.

“She was quite the collector,” I said.

Mrs. Persky winced. “I’m not sure Cynthia intended to save all this. She merely left it behind.” She lifted a glove, considered it. “By the time my baby ran away, her childhood was already long gone.” Her words had the odd, scripted quality of someone who has repeated a confession to herself a thousand times. I wanted to press against her comfort zone, crack open the truth. But you can’t bully your way to candor.

I said, “Mr. Elkaim gave me the impression that Cynthia was…not really some crazy runaway. He said she was really a very good girl.”

“She was too good. And too knowing.”

“Yeah?”

“Yes, unquestionably.” She sat herself in the desk chair. She was relaxing around me in little increments.

“What did she know, exactly?”

“What kind of a marriage her parents had, how terribly restless I was. Now I understand that it shut her down—having a mother so…wanton.” She said the word flat, without guilt or boast. She idly picked up the bunny rabbit, touched his blank button eyes. “But when she was here…I didn’t see her, not really. And so she did what any invisible person should do, she ran. But I still didn’t grasp how badly her heart was broken—I…I had to identify her body, up north. It was only then that I understood how badly I had failed her.” Then, as if waking from a hazy dream, she turned to me and said, “Young man, just what is it you are trying to figure out?”

“Mrs. Persky, why do you think Emil Elkaim killed Reynaldo Durazo? I mean, are you sure he did?”

“I didn’t see it happen. But I would be lying if I said it was impossible. It’s taken me years to admit that—because I adored Emil.”

“Really.”

“Absolutely. Emil was marvelous. He was just what this house needed. He was all life. Health. Vigor. Even Herb could not deny—he was infectious.” Again, there was something not quite spontaneous in her tone, and she sensed that I sensed it. “If you want to know the truth,” she went on, “I think all three of us were a little bit in love with him. Well, she was madly in love with him. But Herbie and I each were crazy for him in our way too.” She smiled for the first time, almost blushed at the memory. I surged with the desire to tell her I agreed, but she was on a roll. “Oh, Emil was a mess. Sometimes he wore shoes, sometimes he couldn’t be bothered. Sometimes his hair was combed back, sometimes it was all over his face like a shaggy dog. He knew immediately that my husband was different—and he didn’t care one bit. He was utterly without judgment. He flirted with me, too. Wildly.”

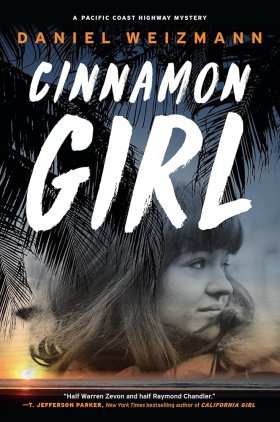

“Not too fun for Cinnamon.”

“That’s what you think, but she loved it. Because he was hers, totally. Believe me, for all my faults—and I was never a saint—I wouldn’t have dared steal her happiness.”

I didn’t remark that somebody did.

“How about Durazo,” I said, “the victim?”

She shrugged the apologetic shrug of progressives. “I didn’t know him. Later, of course, I learned he was a troubled boy.” And then, conspiratorially, she added: “Is it possible to be sixteen and not be troubled?”

“Sure, but…did Emil have any kind of reason to kill him?”

“I can’t imagine. I still get letters from the victim’s cousin—she’s a professor at UCLA, a very persistent woman.”

“Letters about what?”

“Well, she wants the police department to reopen the case, of course. As if that’s going to bring back our loved ones.” With this, Mrs. Persky bent and reached under the folded sweaters and miniskirts and pulled out an old purple lock diary. “Here,” she said. “The pièce de résistance.”

“Do you have a key for this?” I said.

“It’s been broken for years. Open it.”

No words, just sketches—cat-eyed teen girls in miniskirts and mod poses.

“Not a very scintillating read I’m afraid,” Mrs. Persky said. “But teenage girls are like cats. They feel things but they don’t know why. They purr. But they haven’t yet got the words.” She shot me a deep look, loaded with pain. “Some of them never find the words.”

“You’re talking about Cinnamon.”

“In this house? She never got the chance to find her voice.”