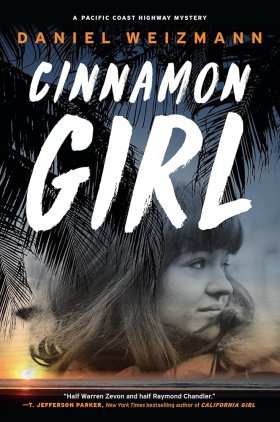

A chill passed over me, juiced by the LAPL heaters. Devon Hawley Senior, eighty-six, lived kitty-corner to Marjorie Persky, Cinnamon’s mom.

They were next-door neighbors.

That meant maybe—no, likely—Devon Hawley Junior grew up across the street from Cinnamon. And if he did, he had to know her. And if he knew her, he knew Emil too.

Forty years later—he shows up out of the blue. “I can prove he’s innocent.”

I checked my watch—it was almost 4:30. I’d let the day get away. With just an hour of daylight left, there was no reason not to drive to Medill Place, see it for myself.

I got up and was about to leave when I remembered the Durazo obit. I went back to the desk. The librarian was scrolling her database with a pout on her cute mug.

“I’m really sorry,” she said. “Amazed to say there’s not one single Reynaldo Durazo obituary in our whole system.”

We exchanged a knowing look: nobody’d written one. They’d effectively wiped him out of human history.

4

4

It was just before nightfall when I arrived at Medill Place—the yellow diamond Dead end sign hit me funny. I parked on the curve of the cul-de-sac and got out. The rains had slowed but the sky was still silver. Three midcentury sprawls faced each other. Number 2825 on the right was the biggest. White curtains hung in the two big windows over a two-car garage, with twin staircases that wrapped around either side to the double front doors. Two of everything—even the bell ding-donged twice. A housemaid wearing earbuds opened the big doors and turned off her vacuum cleaner with a keen look of interruption. She yanked out an earbud long enough for me to ask for Mrs. Persky.

“Is she expecting you?”

“Nope—but she’ll want to speak with me.”

It was a bit of wishful thinking and the maid seemed to know it. She disappeared and Marjorie Persky came in from the open-air kitchen with guarded curiosity and a crossword magazine in her hand. She was striking for seventy-eight—even the pearl granny glasses dangling from her neck were part come-on.

“How can I help you?”

“I’m sorry to intrude like this, Mrs. Persky, but your phone number’s not listed. My name’s Adam, ma’am. I’m an investigator working for Charles Elkaim.”

“Oh.” The name chilled her. “How is Charles?”

“Not that great,” I said. “He’s getting up there…and he may not have much time.”

“What can one say. When it’s one’s time, it’s one’s time.” She spoke sternly, but her face fought the natural veer toward empathy. “And what do you expect I can do for you and Mr. Elkaim?”

“That’s a good question,” I said. “Truth is, I’m not sure. Right now, I’m just trying to get a better sense of…what happened here.”

“Murder happened here,” she snapped. “Right here on my property, thirty-eight years ago. And it destroyed my family.”

I wanted to tell her that I’d met her daughter—long ago. That we’d gone to Disneyland in another lifetime. That she was my first monster little boy crush. But I knew it would make me sound like a crazy person.

“I do know that, Mrs. Persky, I—”

“Well then, what on earth gave you the gall to come here?” Her voice went shrill all at once. “You do also know my daughter is dead?”

The maid reentered and shot her boss a concerned glance.

“I’m fine, Alba. Please give us some privacy.” Alba smiled a fake one and split—Mrs. Persky watched her like a general. The commanding allure of these older broads tumbled by the Hollywood machine was a force to be reckoned with. “Now. What does Charles Elkaim want from me?”

“Mrs. Persky,” I said, “please don’t hold my visit against Mr. Elkaim. This wasn’t his idea.”

“I don’t blame Charles for what befell all of us—Adam. But I certainly don’t have any comfort to offer him.”

“Maybe it’s not comfort he’s looking for,” I said. “If you ask me, I think he’s desperate to let go.”

A wry, wicked smile crept over her face. “So he’s having trouble letting go, is he?”

I nodded. I’d touched a nerve.

“Let me show you something, young man. Come, follow me.”

Mrs. Persky led me through the house, past the ancient living room with its polished black piano resting alongside an easel with a blank canvas. She flicked her magazine onto the couch as we passed.

“Do you play?” I said.

“Rarely,” she said with restrained malice.

I followed her up a curving white staircase and down a white hall. We came to a door covered in big pink and baby blue dots.

“Here’s the last of my pretty Cinnamon—same as the day she left us. That is called not letting go.”

She opened the door and we stepped inside a shrine to pop art, blazing with color. Posters of Lichtenstein’s Drowning Girl and Peter Max’s butterfly and Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones handing a child a balloon covered the walls. One corner over the bed was a crazy makeshift collage of pages torn from Vogue and Cosmo, but all from the sixties—Twiggy, Jean Shrimpton, Catwoman, Mary Ann from Gilligan. And interspersed with the slinky models were covers torn off a comic book called Little Dot Dot-Land, a little girl pouring polka-dot maple syrup over polka-dot pancakes, taking a polka-dot bath, walking in the polka-dot rain. On the lime-green bureau sat a polka-dot box of 45s and a rinky-dink one-piece Fidelity record player.

As if reading my mind, Mrs. Persky said, “I know, strange for a child of her generation. But my daughter loved vintage fashion. She was absolutely obsessed with the nineteen sixties.”

“Maybe because you were her age in the sixties.”

“I don’t think so.” She scanned me for sensitivity. “Cynthia was born to the wrong era. Like her father.”