I could not find a word to say.

“A revenge slaying,” he went on. “And Emil’s girlfriend—”

“She—ran away?”

“Yes. A few months later. And she died of an overdose.” His black eyes bore into me like a telescope scanning for something just one yard away. “In 1987.”

“So awful, Mr. Elkaim, I am so—”

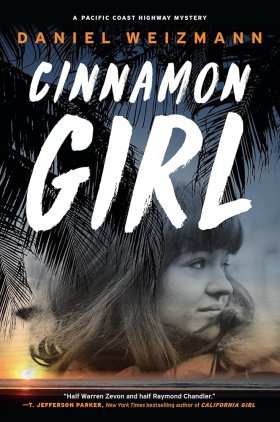

“In any case,” he interrupted as if to go on—but then he reached into his brown coat pocket and handed me a folded-up printout of a scanned photo: a fading Kodak shot of Emil and his girlfriend Cinnamon on the Santa Monica Pier, arm in arm outside the Skee-Ball Arcade. Emil was shirtless in flip-flops and cutoff jeans, his grin teenage goofy. Cinnamon was laughing too, in a white-and-yellow minidress that blazed bright in direct sunlight. But they looked more like sixties teens than kids of the eighties. It wasn’t quite how I remembered them. “What year was this taken?” I asked.

“1983,” he said. “In the summer. Her real name is Cynthia. Was Cynthia.”

“But everyone called her Cinnamon,” I said.

“That’s right.”

His old man’s nod packed a punch—regret, loss, guilty-feeling erotic charge, and the peculiar wistful hands-off pleasure some fathers get from seeing their sons with pretty girls. Then, as if to back off it, he said, “She…loved to sing with us. Shabbat, at the dinner table.” But she was something else, reflecting back the sunshine. Even from this faded printout scan of a faded snapshot, the feeling came back to me: these two were gone for each other, you could practically see little birds flying around their heads. I returned the printout, and he refolded it.

“Three weeks ago, a man came. On a Saturday in the morning. I was not expecting anyone. I came out of the shul here and sat with him in the lobby. He called himself Devon Hawley. He was perhaps in his fifties, maybe more. He claimed that he had known my son in high school. I did not remember him, but I had no reason to doubt him. He gave me this.”

Elkaim dug into his coat’s other pocket and pulled out a folded newspaper page. He opened it for me, a page-long article torn from the Downtown Courier—“Miniaturist is City Dreamer.” In the center of the article was a black-and-white photo of a cheery-looking bald man hovering over a miniskyline like a middle-aged Godzilla.

I scanned quick:

For Devon Hawley, Jr., the creation of finely detailed tiny cities is more than a hobby, it’s an obsession. In just the last three years, Disney, NBC/Universal, Pixar, and Netflix have all called upon Mr. Hawley and STEAM-WORLD STUDIOS here in DTLA, to design and photograph the backdrops for over a half-dozen blockbusters.

I looked up. “Did this man harass you?”

“Not in the slightest. He was very polite. Tall like the day is long.” Elkaim made a reaching gesture. “He was apologetic for having interrupted me and so forth. Quite nervous.”

“What makes you say so?”

“He spoke in a halting manner. He seemed to have a hard time looking me in the eye.”

“Isn’t it a bit strange that you didn’t remember him?”

“No, no, I don’t think so. My son had a life of his own—especially as a teenager.”

“Okay,” I said. “But what did this Hawley guy want?”

“He told me…that he could prove my son’s innocence. He said he figured things out.”

“Wow, all these years later?” I sat up, on instinct. “Did…did he say how?”

“No.” Elkaim pursed his dry lips, tallying some invisible calculation. “No, he would not tell me how he knew, but my lifetime of suspicions were confirmed. I always knew it was a mistake. My son was not capable of murder.”

“Of course, but—”

“The night they arrested Emil, he wept to me, he told me he was innocent. He would not lie to me about such a thing.”

I took it in—I knew I was on shaky ground. Everybody’s son is innocent.

“So…this guy just came here out of the blue, without any notice and—”

“But he was not rude about it. He simply said that he wanted to introduce himself and set up a time to speak, to share certain details. He asked if he could return the following Saturday—to take me to his studio, I gather to show me his…his files, his evidence. He begged that I tell no one. As I say, he seemed very nervous. But respectful about the whole matter. And then—” Mr. Elkaim raised his palms to the heavens. “—a no-show.”

I scrambled for words of comfort, came up short. “Maybe he got the dates wrong?”

“At my age, one does not have time for such delays.”

“I understand, Mr. Elkaim—”

“No,” he said firmly, “you do not understand. A cancer eats my pancreas. The doctors say I have three months, six at most.”

A bright, vivid silence—

“Ninety days,” he added without self-pity. But his dark eyes held me in place.

“I want to help,” I said. “Anything I can do. But…I’m trying to get a full picture. Can you tell me exactly what this man said?”

“Word for word, no. I was in a state of shock. I…I was shaken, I did not want to press him, I—”

Elkaim hesitated and, before my eyes, his yearning morphed into a peculiar self-scrutiny. His longing for justice, for last-minute redemption was high, wild, out of control, and he knew it. It made both of us uncomfortable, this intensity of hope. I caught myself glancing at the glass door. Like more than one visitor to a nursing home, I yearned for the clock to move quicker.

Uncle Herschel is watching—

“Mr. Elkaim,” I said gently, “people do prey on the elderly—we know that.”