“Lazar Lawrence,” he said. “That’s my birth name. But it just confuses people, so everybody calls me Larry Lazerbeam.”

“I see.”

“This guy doesn’t care about your name,” his wife said. “He isn’t from the census bureau.”

“Right, right,” Lazerbeam said nervously. “This guy wants to know about The Daily Telegraph.” He turned to his wife and pointed. “I told you their time would come!”

“Actually,” I said, “I’m looking into…Emil Elkaim. I’m working for his father.”

“Ohhhhhh, I see. Reality TV stuff. Yeah, well—you won’t find the dirt on poor old Emil here, man.” He let out a low moan. “What can I say? Tragedy.”

“But…was Emil in the band?”

“Sure was,” Lazerbeam said.

“He was the guitarist,” his wife chimed in. “Good-looking boy.”

“Were…you Pioneer Records?” I asked.

“Well, yeah,” Lazerbeam said, mock-humble. “We practically invented the indie thing.”

“Oh boy, here we go,” his wife said.

“But you see,” Lazerbeam said, unruffled, “If we’re talkin’ Telegraph, what you gotta understand is, these were high school kids. Young kids. And they wanted to be part of this bigger scene.”

“What scene is that?”

“Oh, the paisley underground, man, the mod scene, the big revival.”

He pulled back into the space next to me and threw his dirty sneakered feet on the small coffee table, reached into his musty shirt pocket and pulled out an orange Bic mini-lighter.

“Mind if I make like Bob Marley and light a fire?”

I shook my head, but his wife let out an exasperated sigh and took off for the bedroom.

“Don’t mind her,” he said, reaching for the roach in the ashtray. “She’s got issues.”

He sparked up and sucked the last life out of that tiny thing. It was a darn small space to be smoking—I braced myself for a contact high—but he didn’t blow much smoke.

“The ’Graph is what I called ’em way back in the day,” Lazerbeam said. “And when I say these were kids, man, I mean they were really practically children. Ambitious for their age, but there was a lot of excitement going on then. And they wanted in on the action.”

“This…paisley underground?”

“That’s right, you never heard about it?”

I shook my head.

“It was the thing, man—”

“And it was all about the sixties?”

“That’s right.”

“But this was during the eighties.”

“Exactamundo,” he said, offering me a hit. When I shook my head, he licked his big, calloused thumb and put the roach out. “We wanted to stop the wheel, you see what I mean? We didn’t like the eighties. We didn’t like where things were heading.”

“So you—”

“So we turned back time, man—with religious fervor. We didn’t just want to ape the 1960s. We wanted it to be the 1960s, for all eternity.”

“So was this, like, a psychedelic rock kinda thing?” I asked.

He shook his head every which way in frustration. “The music wasn’t even half of it, man. We were about a sensibility. A resurrection. We collected verification of our correctness—’cause we knew. And we studied our archives like they were scripture—we believed in the past, you know what I mean? And not the ancient past, mind you. We weren’t classical music snobs. We believed in the recent past, like, twenty years out of reach.”

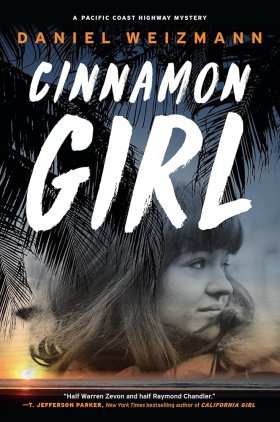

I thought of Cinnamon Persky’s bedroom and a chill ran through me.

“So where does The Daily Telegraph fit into all this?” I said.

“Oh, it was just destiny, man,” he said, his big, red-tinged eyes aglow like fireballs. “From the second I heard ’em. You see, my old man owned the newsstand on Hollywood and Las Palmas, heart of the heart. So I was, like, used to being on the cultural edge, if you know what I mean. And working the newsstand—that’s almost like being onstage, right? My pops had all kinds of side hustles. He used to deliver Variety and Hollywood Reporter to Screen Gems over in Burbank every morning, 5:30. When I was seven, eight years old, someone talked Pop into the extras game—in sixty-five, he started helping to drum up dancers for the Shebang show, you know, scouting the teenyboppers, and Dad was quite the salesman. He talked up every cute chick that walked by that newsstand, and I just sat there amazed, watching him work.” Lazerbeam’s eyes glossed with almost tears. “Can you dig it? My dad made it happen, man.”

During the course of this impassioned monologue, Lazerbeam’s wife had meandered back to the tiny kitchen. She was pretending to look for something in the cupboards, but she was in no hurry to find anything, and I could vibe her taking us in, wanting and not wanting to participate.

“So,” I said, “then you helped spark this sixties revival. And The Daily Telegraph were part of that.”

“You got it, kiddo. I learned how to put my ear to the ground. In fact, Pioneer was going to put out the original Bangles single back when they were called The Bangs but—”

“Oh, please,” his wife interrupted. “You had one conversation with one Bangle for, like, three minutes.” And then, to me: “It’s pathetic. For a man who considers himself some kind of world-class historian, Larry misremembers every damn moment he ever actually lived through.”