This caught my attention. “The freest?”

“Today, people don’t compete over that so much, but back then? It was the main thing. You were either uptight or you were outta sight. It wasn’t how rich you were, how powerful you were. It was, can you really be free, man? Like, in your vibe, your spirit? That was everything. No greater shame than not being free.”

As he spoke, I eyeballed the remotes in his hands. He was rewinding, about to play the clip a fourth time.

I said, “Listen, man, I gotta split soon. Any chance I could take a look at that Telegraph stuff?”

“Oh yeah, of course, man, of course.”

He turned off the television and put the lights on. We turned our attention to the mess on the table. He started shuffling through things, fighting distraction. Then he pulled out a great big poster board with a tissue overlay held on by white tape—it had to be about thirty inches long and more than a foot wide.

“This was it, man,” he said, and then, more quietly, “Greatest failure of my life. They…didn’t want me to put out the wax.”

“They?”

“The band, man. After everything. Plus, I didn’t want to exploit the situation.”

“Oh right,” Marie said. “Johnny Virtue over here.”

“Believe me,” he said, “there were some jackasses who thought I should take advantage. Put the newspaper stories on the album cover. Drummer murdered, film at 11. No go, couldn’t do it.”

“Wait,” I said. “Reynaldo Durazo was their drummer?”

Lazerbeam looked at me incredulous in the afternoon trailer stillness. “Of course. Him and Hawley were the main songwriters. Then when Emil was killed—I knew I had to leave it alone.”

“Oh, it was awful,” Marie said.

“Awful,” I repeated, blindsided, as he peeled back the tissue and then there it was, improbable that it had survived but it had: a mocked-up album cover, front, back, and spine, laid out on graph paper with penciled printer’s instructions along the side.

DEL CYD THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

My heart thumped at the sight of it—a thing of crazy beauty. On the right, the front cover, a haphazard collage—cutouts of Cyd Charisse dancing in white, in repeating echoes, surrounded by wide-eyed tropical fish swimming in every direction, xeroxed moons, hand-drawn Twilight Zone swirls and grinning Cheshire cat heads…handmade psychedelia redux on a budget. You could still see the mucilage smears on the sides of the collage.

And on the left, the back jacket—a single large photo of the United Nations of Skinny Teenage Boys, with the hills of Bronson Canyon behind them laying supine like a resting woman. You could picture a B-movie flying saucer coming over those curvy slopes. But these guys had no quarter with sci-fi. They dressed like characters from a 1960s TV Western and stood in poses of strange casual mock seriousness—a dome-haired guy, a frizzy-haired Black dude, a blond saturnine boy with golden curls, and a Hispanic kid so young he looked like he’d accidentally wandered into the frame from the local soda fountain.

And then—Emil, the Emil I knew, with an interrogating half-smile. The handsome bastard—a ripple of heartbreak ran through me.

I tapped the photo gently.

Lazerbeam pulled at his beard. “Yup, that’s Mr. Emil, the Elk. He played guitar.” Then he pointed to the young one. “And that’s Rey, the drummer—the one who…you know. This is Jeff Grunes on bass, we stay in touch a little. He works for the LAUSD. And this is Mickey Sandoz, the singer.”

There was something jarring about skinny dark-dome-haired Sandoz—he was menacing, disgusted, deliberately elsewhere.

“Mickey was a trip,” Lazerbeam said. “Fucking ego like you wouldn’t believe. You know, he basically thought he could replace the whole band and it would still be…him, the main attraction. And he didn’t even write the songs, man. They don’t call it lead singer’s disease for nothing.”

“Where’s he nowadays?”

“Where else, doing hard time—ten years in Banning for moving meth.”

“Worst kind of junkie,” Marie said with tight apprehension. “Just a user through and through.”

“One time,” Lazerbeam said, “years ago, I saw him turning tricks on Santa Monica and Crescent. I wanted to pull over, ask him if he needed a meal or something but…”

Lazerbeam gave an apologetic shrug.

“Wow,” I said. “And…whose this one…with the blond curls?”

“That’s Hawley, the keyboardist.”

I said, “Where’s he these days?” in the flattest voice I could muster.

“Oh, he’s a big-timer. Set design, features, television. He really made it.”

I faked casual, sleepy eyed, but my mind was going off in three directions at once.

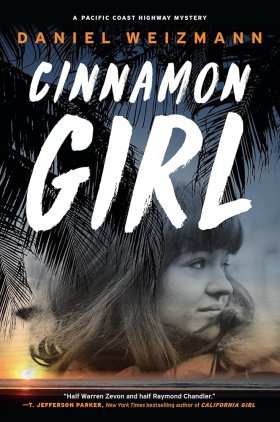

“What about Cinnamon, Emil’s girlfriend?” I asked. “Did you two know her?”

They looked at each other questioningly.

“Cinnamon?” Lazerbeam said. “I don’t remember anyone by that name.”

Marie said, “Wait, was that the neighbor girl?”

“That’s right,” I said. “Cinnamon, Cynthia. She lived across from Hawley. You guys never crossed paths?”

They glanced at each other again, some quick discomfort crackled between them.

“Look, we stayed out of their personal lives,” Lazerbeam said. “Our thing was the music.”