The Beachcomber

Mark Toner

SF Caledonia

Monica Burns

This article will be the first of a regular column in Shoreline of Infinity, in which I will explore Scottish science fiction from across the centuries. I hope to discover what could be named as the oldest piece of Scottish science fiction there is.

Along the way, there will be some surprises: authors you wouldn’t normally regard as SF writers (like John Buchan in Issue 1) and some stories that the modern reader may be able to be re-evaluate as science fiction. Scotland has produced some top-class and very often influential SF writers. So instead of stripping away national identity, this column will celebrate the many, often overlooked, examples of good Scottish science fiction.

The first writer I happened upon was David Lindsay (1876-1945), author of A Voyage to Arcturus.

Monica Burns is one of our talented illustrators, but she is also taking a Masters in Creative Writing at Aberdeen University. As we got talking, it turns out she too is curious about science fiction in Scotland so we set her a challenge; what are the earliest examples Scottish science fiction? Who wrote them? What can we find out about them? Monica accepted the challenge, which, it seems, is turning into a quest.

—Editor

David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus (1920) is a daring, epic adventure. It is a philosophical exploration of good and evil, the soul, and the very nature of existence. Some modern critics have put it in league with Alasdair Gray’s Lanark, published 60 years later and now lauded as a modern Scottish classic. In spite of its recognition now, the novel has never had a place in the mainstream. In David Lindsay’s lifetime, A Voyage to Arcturus sold very few copies. Throughout the 20th century, the book was found under labels like ‘cult classic’ or ‘underground’—which makes it sound very inaccessible. A Voyage to Arcturus shouldn’t be cast off because it is considered a cult book. It is written in fluid prose that’s easy to read, and the adventure itself is uncomplicated despite all the bizarre, imaginative things Lindsay creates in the novel, such as new colours in the colour spectrum, ulfire and jale—you will be surprised how easily you can almost see them.

At its most basic level A Voyage to Arcturus is a journey through an alien planet. It gives so much more, however, than just a simple quest story. Lindsay has taken world-building to an exceptional level. On his planet, Tormance, he creates many branches of philosophy and spirituality, creeds and ways of life, along with all the complex conflicts that come with each of these.

The esteemed literary critic, Harold Bloom, whose academic work spans the vast canon of literature from Chaucer to Kafka, liked A Voyage to Arcturus so much that his only fictional novel was a quasi-sequel of Arcturus, called The Flight to Lucifer. It has been said that A Voyage to Arcturus also greatly influenced the work of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R Tolkien.

The story begins in Hampstead, London, with a séance. In front of a horrified audience, the medium summons a spirit: a strange otherworldly young man takes shape before their eyes. The séance is violently brought to a halt as a stranger bursts in. He calls himself Krag, and he seems to know about this spirit, claiming he has been to its native realm. Maskull, the story’s hero, and his friend Nightspore, accompany Krag outside into the street where he tells them of adventures he could offer. They go with him to the north-east coast of Scotland, to an old observatory. From there they are to fly in a crystal ship towards the brightest star in the northern hemisphere of our sky, Arcturus. Krag claims that an inhabited planet called Tormance orbits Arcturus, and that he must go there.

When they land on Tormance, Maskull awakens to find himself separated from his friends. Meeting native people along the way, he navigates his way through this bizarre world seeking answers. He finds his strength, faith and morals tested to the extreme.

The novel is largely philosophical. It has been compared to Dante’s Divine Comedy and John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress: allegories from the 14th and 17th centuries. Although it is a 20th century novel, A Voyage to Arcturus harks back to the medieval tradition of allegory—a literary device where the characters, landscape and interactions are more symbolic than realistic because they contribute to an overarching spiritual or moral message. The characters personify certain moral viewpoints in order to test the protagonist. You can forgive Lindsay for not populating his book with psychologically complex characters like we’re used to encountering in modern literature, because it is intriguing to guess at what the characters represent, and what lesson Maskull is supposed to learn from them. Like any good philosophical text, and indeed any good SF story, it will have you pondering late into the night.

If that is not your cup of tea though, the philosophical element isn’t so heavy handed that nothing else is enjoyable. For one, the novel’s setting is incredible. It is a feast for the imagination. Even if you just want to skim through the book, Tormance is an excellent place to explore. There are bizarre creatures, strange incidences and sublime landscapes. There is more than enough to keep any reader entertained.

Many critics have remarked on the “strange genius” of the man behind Arcturus. Lindsay was a shy, bookish person, and little for definite is known about his life. He was born to a Scottish Calvinist family in 1876, and spent a lot of his life in the south of England. Every year he would holiday in the Borders, from where his family had originally hailed, and was educated for a time in secondary school in Jedburgh.

When his father left his family, young Lindsay was made to give up his university scholarship to help earn money for his family. He spent twenty years as an insurance broker in London. The outbreak of WW1 interrupted his literary career further, and so it was only when he moved to Cornwall after the war that he was able to become a full time writer at the age of 44. A Voyage to Arcturus was published in 1920.

His next publication was science fiction too, although it explored a different kind of space. The Haunted Woman, published two years after Arcturus, is set up like a thriller. It has a familiar 1920s setting with seaside resorts, betrothals and scandal, open-top cars and manor houses, but with a disturbing supernatural twist. Isbel and her fiancé seek to buy an old manor, Runhill house—a place steeped in myth and folklore. But the house emits eerie music that only certain people, like Isbel and Runhill’s owner, Mr Judge, can hear. They find phantom staircases and floors of the house that don’t exist. Isbel and Judge are drawn to the mysteries of Runhill and have to discover its secrets together.

Unfortunately, The Haunted Woman did not sell well either, despite Lindsay’s attempt at making it a more ‘commercial’ novel than Arcturus. Perhaps Lindsay was born into the wrong time; a metaphysical fantasy love story like The Haunted Woman would likely be popular if it was published today. In any case, Lindsay’s science fictional philosophical novels deserve more credit than they currently get.

When you read A Voyage to Arcturus, go in with an open mind. Engage with it. Be ready to be baffled. Don’t expect cheap sensational thrills for the sake of it. This is no pulp fiction. This book will be best enjoyed while reading, and after reading, if you connect with it. Get the deeper cogs of your brain grinding and search with Maskull for the ultimate truth. Religious or atheist or anything at all, you’ll get something out of this book. It has done its job if it has made you think.

A Voyage to Arcturus

David Lindsay

Chapter 6: Joiwind

This extract is Chapter 6 of A Voyage to Arcturus. In the previous chapter, Maskull and his companions, Nightspore and Krag, travelled from Starkness in the north of Scotland to the planet of Tormance. Maskull fell unconscious during the journey, and so remembers little past taking off from the observatory.

The whole expedition is shrouded in mystery. Maskull knows very little of why they travelled to Tormance. When questioned, Krag has been cryptic and Nightspore evasive in his answers. All the information Maskull can get from them is that they are in pursuit of a mysterious man called Surtur.

At the start of this chapter, Maskull first awakes on Tormance, naked and alone in the middle of a desert, with his friends nowhere in sight.

It was dense night when Maskull awoke from his profound sleep. A wind was blowing against him, gentle but wall-like, such as he had never experienced on earth. He remained sprawling on the ground, as he was unable to lift his body because of its intense weight. A numbing pain, which he could not identify with any region of his frame, acted from now onward as a lower, sympathetic note to all his other sensations. It gnawed away at him continuously; sometimes it embittered and irritated him, at other times he forgot it.

He felt something hard on his forehead. Putting his hand up, he discovered there a fleshy protuberance the size of a small plum, having a cavity in the middle, of which he could not feel the bottom. Then he also became aware of a large knob on each side of his neck, an inch below the ear.

From the region of his heart, a tentacle had budded. It was as long as his arm, but thin, like whipcord, and soft and flexible.

As soon as he thoroughly realised the significance of these new organs, his heart began to pump. Whatever might, or might not, be their use, they proved one thing that he was in a new world.

One part of the sky began to get lighter than the rest. Maskull cried out to his companions, but received no response. This frightened him. He went on shouting out, at irregular intervals—equally alarmed at the silence and at the sound of his own voice. Finally, as no answering hail came, he thought it wiser not to make too much noise, and after that he lay quiet, waiting in cold blood for what might happen.

In a short while he perceived dim shadows around him, but these were not his friends.

A pale, milky vapour over the ground began to succeed the black night, while in the upper sky rosy tints appeared. On earth, one would have said that day was breaking. The brightness went on imperceptibly increasing for a very long time.

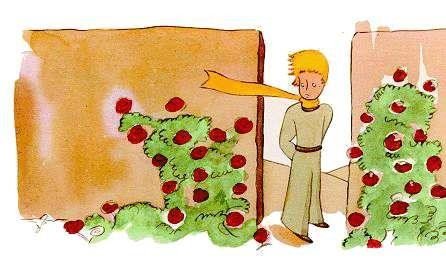

Maskull then discovered that he was lying on sand. The colour of the sand was scarlet. The obscure shadows he had seen were bushes, with black stems and purple leaves. So far, nothing else was visible.

The day surged up. It was too misty for direct sunshine, but before long the brilliance of the light was already greater than that of the midday sun on earth. The heat, too, was intense, but Maskull welcomed it—it relieved his pain and diminished his sense of crushing weight. The wind had dropped with the rising of the sun.