1.I reject the stigma associated with mental healthcare. I value my mental health and see seeking help as an act of strength and self-love.

2.I honor my roots by incorporating ancestral practices along with traditional mental healthcare. Both are valuable and contribute to my holistic healing journey.

3.I deserve therapy that is culturally sensitive and representative of my lived experience. I commit to seeking such support and advocating for its importance.

4.I acknowledge the healing power of shared experiences and storytelling. I am open to the support and community offered by group therapy.

5.I embody the principle of Ubuntu, recognizing our shared humanity. My well-being is interconnected with the well-being of others.

6.I acknowledge the impact of systemic racism on my mental health. I am resilient and will continue to strive for healing and justice.

7.I will work to build trusting relationships with healthcare providers who respect and understand my experiences. I will advocate for my needs and my care.

8.My spiritual beliefs nourish my mental well-being. I honor the role of spirituality in my journey to emotional health.

9.I will share the importance of mental health with younger generations, creating a safer and more supportive future for them.

10.I acknowledge the power of rest and self-care in supporting my emotional well-being. I will prioritize these essential aspects of my mental health journey.

56.“How diverse is the psychology workforce?” n.d. American Psychological Association. Accessed August 6, 2023. www.apa.org/monitor/2018/02/datapoint.

57.Powell, Wizdom, 2022. “Healing Trauma to Improve Emotional Wellbeing in Black Communities.” Interview by Elizabeth Leiba. EBONY Covering Black America Podcast Network. open.spotify.com/episode/2qEOeysSzZm9de7t5SU8sA?si=1ef9cfac33ab47d0.

58.Mthombeni, Zama Mabel, 2022. “Xenophobia In South Africa,” The Thinker (93), 4:63–73. doi.org/10.36615/the_thinker.v93i4.2207.

59.Barbour, Shannon. 2020. “Accessible Mental Health Resources for Black Women.” Cosmopolitan. www.cosmopolitan.com/health-fitness/a32731463/mental-health-resources-for-black-women/.

60.Whaley, Arthur L., 2020. “Associations Between Seeking Help From Indigenous Healers and Symptoms Of Depression Versus Psychosis In The African Diaspora Of The United States,” Counselling and Psychotherapy Research (21), 1:179–187. doi.org/10.1002/capr.12313.

61.Kirmayer, Laurence J., Stéphane Dandeneau, Elizabeth P. Marshall, Morgan W. Phillips, and Karla Jessen Williamson, 2011. “Rethinking Resilience From Indigenous Perspectives,” The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry (56), 2:84–91. doi.org/10.1177/070674371105600203.

62.Lee, Boon-Ooi, 2023. “Journeying Through Different Mythic Worlds,” International Perspectives in Psychology (12), 2:96–111. doi.org/10.1027/2157-3891/a000072.

63.Nare, Neo and David D. Mphuthi, 2018. “Conceptualisation Of African Primal Health Care Within Mental Health Care,” Curationis (41), 1. doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v41i1.1753.

64.Whaley, 2020.

65.Kpobi, Lily and Leslie Swartz, 2019. “Indigenous and Faith Healing In Ghana: A Brief Examination Of The Formalising Process And Collaborative Efforts With The Biomedical Health System,” African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine (11), 1. doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.2035.

66.Thornton, Robert, 2009. “The Transmission Of Knowledge In South African Traditional Healing,” Africa (79), 1:17–34. doi.org/10.3366/e0001972008000582.

67.hooks, bell and Bell Hooks, 1995. “Sisters Of the Yam: Black Women And Self-recovery.” African American Review (29), 3:529. doi.org/10.2307/3042416.

68.hooks and Hooks, 1995.

69.Barbour, 2020.

70.McAfee, Melonyce. 2022. “The Nap Bishop Is Spreading the Good Word: Rest.” The New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2022/10/13/well/live/nap-ministry-bishop-tricia-hersey.html.

71.Harrell, Shelly P., 2000. “A Multidimensional Conceptualization Of Racism-related Stress: Implications For the Well-being Of People Of Color.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry (70), 1:42–57. doi.org/10.1037/h0087722.

72.Angelou, Maya. “All God’s Children Need Traveling Shoes.” New York: Random House, 1986.

73.Hankerson, Sidney H. and Myrna M. Weissman, 2012. “Church-based Health Programs For Mental Disorders Among African Americans: a Review,” Psychiatric Services (63), 3:243–249. doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100216.

74.Bogart, Laura M., Bisola O. Ojikutu, Keshav Tyagi, David C. Klein, Matt G. Mutchler, Lu Dong, Sean Jamar Lawrence et al., 2021. “Covid-19 Related Medical Mistrust, Health Impacts, and Potential Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black Americans Living With HIV,” JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (86), 2:200–207. doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000002570.

75.Whaley, Arthur L., 2001. “Cultural Mistrust and Mental Health Services For African Americans,” The Counseling Psychologist (29), 4:513–531. doi.org/10.1177/0011000001294003.

76.“The US Surgeon General’s Advisory.” 2021. HHS.gov. www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf.

77.Stone, Deborah M, Karin A Mack, and Judith Qualters, 2023. “Notes From the Field: Recent Changes In Suicide Rates, By Race And Ethnicity And Age Group—United States, 2021,” MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (72), 6:160–162. doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7206a4m https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7206a4.htm.

78.Stone et al., 2023.

79.“To Support Black Youth Mental Health, We Must Look to Community-Based Solutions.” 2023. The Jed Foundation. jedfoundation.org/to-support-black-youth-mental-health-we-must-look-to-community-based-solutions/.

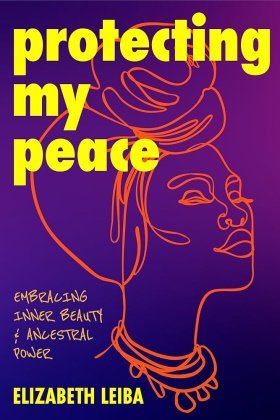

chapter 5

the importance

of protecting

personal peace