“Battle of Zama” (Scipio’s defeat of Hannibal, 202 B.C.) Anonymous (circle of Giulio Romano), ca. 1521 Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Russia

Giraudon/Art Resource, NY.

OVID’S METAMORPHOSES

Ovid (Publius Ovidius Naso) was born to a wealthy equestrian family on March 20, 43 B.C., the year of Cicero’s death and the year after the assassination of Julius Caesar. His father sent him to study in Rome and Athens, hoping the young man would embark upon a career in law and politics. But Ovid was far more inclined to literature, and in his early 20’s he published his first books of verse (begun when he was only a teenager), the Amores, sprightly elegiac poems written to and about his fictional mistress, Corinna. Though quite self-consciously following the tradition of Catullus, Tibullus, and Propertius (these last two friends of his), his elegies were at once more contrived and more playful, almost a parody of his predecessors’ work.

“Whatever I tried to compose became verse” (quod temptabam scribere versus erat), Ovid later wrote (Tristia 4.10), reflecting back on his career. And indeed he was an enormously prolific poet, publishing one book after another over a period of more than 40 years; most of his early work was sportively erotic, in the manner of the Amores, including: the Heroides, verse epistles from famous mythological heroines to their absent husbands or paramours (e.g., Medea to Jason, Dido to Aeneas); the only partially extant Medicamina Faciei Femineae, a how-to manual on ladies’ cosmetics; the Ars Amatoria, another tongue-in-cheek didactic poem on how to attract and seduce a lover, with two volumes of instructions (some rather naughtily detailed) for men and another for women; and then, aptly concluding the series, the Remedia Amoris, a handbook on extricating oneself from a love affair, once one has had enough.

If all of this sounds ahead of its time and rather lacking in Roman gravitas, so it was. By the time the “Art of Love” first appeared, ca. 1 B.C., Octavian had long since been proclaimed “Augustus,” his monarchy was firmly established, and his program of moral reform was well underway. In this context, Ovid’s poetry, which routinely trumpeted adultery, travestied the sanctity of marriage, and poked fun at authority, could be easily viewed as subversive. It is not surprising, therefore, that in A.D. 8 Ovid was banished by Augustus to Tomis on the Black Sea. Writing from exile, the poet insists that his relegation was the consequence, not of any crime, but of a carmen and an error; the exact nature of the “mistake” has never been ascertained, but the offending poetry certainly included the Ars Amatoria, and the combined offense was so considerable that neither Augustus himself nor his successor Tiberius gave in to the poet’s unceasing, pleas for a recall from Tomis, where he remained, embittered, until his death in A.D. 17 (the same year that Livy died) at the age of 60.

During the decade of his exile, Ovid continued work on two enormously important poetical works which he had begun earlier, the Fasti and the Metamorphoses. The former, a verse calendar describing the major historical events, legends, and festivals associated with each month of the Roman year, remains an invaluable source for these topics, though we have only the first six books (for January through June). The latter, a rich compendium of classical myths in 15 dactylic hexameter volumes, has remained over the centuries Ovid’s most popular and influential work.

Set in a quasi-chronological framework and woven together with ingeniously crafted interconnections, the Metamorphoses recounts some 250 tales of transformation, from the creation of the world out of chaos to the deification of Julius Caesar. In this carmen perpetuum, as he called his greatest poem, Ovid presents us with dazzling narratives (in many cases the best known, or only, ancient source for a particular myth), which range in tone from the tragic to the comic, the heroic to the grotesque, the patriotic to the erotic, some of them charged with political (and occasionally anti-Augustan) undertones, and all of them providing astute insights into the human condition. A supreme manipulator of the language, Ovid has given us too a production that is remarkably “audiovisual,” abounding in cinematographic effects and with a musicality perhaps unparalleled in classical Latin verse.

The four selections included in this book are among Ovid’s best known. The story of the two star-crossed Babylonian lovers, Pyramus and Thisbe, may have originated in the near east, but Ovid is our earliest source; the two young people (teenagers most likely) were neighbors who, once acquainted, fell rapturously in love, only to have their parents forbid their relationship. At first communicating with each other through a crack in the wall connecting their homes, they soon conspire to slip away for a nocturnal, and ultimately fatal, rendezvous just outside the city. This story of young love and its tragic ending has charmed readers for centuries and was a major influence on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. The similarly ill-fated love of Orpheus and Eurydice was well known to Ovid’s readers from Vergil’s longer and more dramatic narration in the Georgics. The lovely Eurydice dies of a snakebite on her wedding day, and her bridegroom boldly descends into the Underworld to bring her back from the kingdom of the dead; Ovid’s perfunctory retelling, which focuses on Orpheus’ almost legalistic pleading with Pluto and Persephone in Hades, is regarded by many readers as a parody of his Vergilian model.

Also familiar to modern readers is Ovid’s story of Midas, the Phrygian king who, granted one wish by the wine-god Bacchus, wasted the opportunity by asking that all he touched be turned to gold. Ovid’s narration is spectacularly visual, as he shows us the king moving from one object to another, gleefully transforming each into gold, until too late he realizes that even his food and drink and his own body are being similarly metamorphosed. In the tale of the Athenian inventor Daedalus and his young son Icarus, another error of judgment leads to unfortunate, and in this case fatal, consequences; imprisoned by Minos, king of Crete, Daedalus constructs miraculous wings for himself and his son to aid in their escape from the island, and Icarus, with the impetuosity of youth, disregards his father’s warnings and flies too near the sun, thus melting the wax that held together his wings and plummeting to his death in the sea.

“Daedalus and Icarus” Antonio Canova 1779 Museo Correr Venice, Italy

Alinari/Art Resource, NY.

Exhibiting a variety that is characteristic of the Metamorphoses, two of these stories, those of Pyramus and Thisbe and of Daedalus and Icarus, focus on more or less ordinary human beings, their passions and their frailties, while the other two involve the agency of the gods, Bacchus and the king and queen of the Underworld. All involve miracles or transformations. And all are told in Ovid’s lively, fluid, highly visual, and musical style.

Some Aspects of Ovid’s Style

Ovid is one of the easiest of Roman authors to read and enjoy, and students will quickly become accustomed to the peculiarities of his style, many of which are characteristic of Latin verse in general and most of which are commented upon in the notes accompanying the selections below. Following are a few important points to keep in mind, as you begin to read, especially if this is your first extensive introduction to Latin poetry.

Word order: Word order is much freer in poetry than it is in prose, and Ovid is no exception. Words that logically belong together, e.g., an adjective and its noun or a preposition and its object, are often separated for emphasis or some other poetic effect (and, of course, for metrical considerations). For instance, an adjective may appear as the first word in a line and its noun as the last (a device referred to as “framing”), or a noun-adjective pair may even be split between two lines; a prepositional phrase may occur between a noun and its adjective or may itself be broken up by other words, or a preposition may follow its object (“anastrophe”); a relative pronoun may precede its antecedent or be placed late in the clause which it is supposed to introduce, or the antecedent may be attracted into the relative clause. A key word or phrase may be delayed and carried over to the beginning of the next verse (“enjambement”).

“Chiasmus” (ABBA order, e.g., object-verb-verb-object, omnia possideat…possidet aera, “Daedalus and Icarus,” line 187), often used to emphasize some contrast, is a favorite device, as is “interlocked word order,” especially of the ABAB variety (e.g., adjectiveA-adjectiveB-nounA-nounB, una duos…nox…amantes, “Pyramus and Thisbe,” 108); an elaboration of this interlocked order known as a “golden line” places the verb at the center of the line with two adjectives preceding and two nouns following, in an ABCAB arrangement (scelerata fero consumite viscera morsu, “Pyramus,” 113). Sometimes interlocked order is meant to create a “word-picture,” where the words are arranged in a way that suggests visually the image that is being described (obscurum timido pede fugit in antrum, “Pyramus,” 100, where the fearful Thisbe is literally inside the “dark…cave”).

Ellipsis is common in poetry as well (especially omission of forms of sum and the subject of an infinitive in indirect statement), and in Ovid one must frequently supply in one phrase a word from another adjacent phrase. The notes provided along with the text below will often call attention to such devices, but students, in reading and translating poetry, need to be aware of these and other variants of word order and thus be all the more attentive to the word endings that signal syntactical relationships.

Augustus of Prima Porta 1st century B.C. Vatican Museums Vatican State

Scala/Art Resource, NY.

Morphology and syntax: Latin poetry in general is characterized by a wider variety of forms and syntax than usual in prose; again, these are often commented upon in the notes, but students should be generally aware of these differences before beginning to read. The predicate genitive (of description or possession) is commonly used in place of a predicate nominative; the dative is more freely used, often in place of the ablative, as in the dative of separation, the dative with verbs of mixing, and the dative of agent with passive forms other than the gerundive; the ablative instead of the accusative is employed for duration of time, the ablative of route is common, and the ablative of agent is used instead of the ablative of means, for purposes of personification. The so-called “poetic plural” is employed where prose would use the singular; and Greek forms appear frequently, especially with proper nouns.

Common too are: omission of prepositions where prose would require them, especially in place constructions; the use of simple verbs instead of their compounds; use of -ere for -erunt for the third person plural of the perfect indicative; use of the genitive plural -um in place of -oruml-arum.

Rhetorical and poetic devices and sound effects: Ovid employs a wide range of these devices, including anaphora, apostrophe, hendiadys, metonymy, personification, simile, synecdoche, and transferred epithet, many of which are identified in the notes. One of the most musical of Latin poets, Ovid also makes extensive use of alliteration, assonance, and onomatopoeia, as well as the various metrical effects discussed in the next section.

The Scansion and Reading of Ovid’s Verse

In order to associate his poem with epic, Ovid deliberately composed the Metamorphoses in the metrical form known as dactylic hexameter, the same meter employed by Homer in his Iliad and Odyssey and by Vergil in the Aeneid. Like these authors, Ovid meant for his poetry to be read aloud, to be recited (from the Latin word recitare, which quite aptly means “to bring back to life”), hence the importance of such features as alliteration and assonance. But the most prominent sound effect in the poem is, of course, the meter itself; and in order to appreciate fully the work’s musicality and indeed to experience it as the author intended, one must read aloud. The most important step in this regard is also the easiest, and that is, as the late Professor Gareth Morgan remarked, simply to read the words correctly and with attention to what they mean. The point is to read the poem as one would read a story in prose to a group of eager listeners, with proper pronunciation of course, but, in particular, expressively. Read the text aloud in just this way, each time you pick it up (and certainly before you commence the artificial exercise of translation into English), and you will find yourself well on your way to a proper appreciation of Ovid’s poetry; beyond that, one needs to know just a bit about the technicalities of dactylic hexameter verse.

Meter: From the Latin metrum (Greek metron, “measure”), poetic meter is simply the measured arrangement of syllables in a regular rhythmical pattern. In English poetry, meter is based upon the patterned alternation of accented and unaccented syllables (Jáck and Jíll went úp the híll”); the system is called “qualitative,” as it depends upon the quality (stressed/unstressed) of the syllables. Medieval Latin verse works the same way, as we shall see later on in this book. But in classical Latin poetry the meter was “quantitative” (a system borrowed, like much else in Roman verse, from the Greeks), based on the alternation of long and short syllables.

Syllable quantity and elision: The syllables of a word may be long or short, as you learned in your first Latin course in order to know which syllable of a word is accented. A long syllable (indicated here by underlining) is one that contains either a long vowel (e.g., a$$$m $$$—macrons indicating long vowels are provided in the Vocabulary at the end of this book), or a diphthong (ae, oe, ei, ui, au, eu; e.g., $$$$saep$$$$e), or a short vowel followed by two or more consonants or the double consonant x (e.g., $$$$quan$$$$tus). Exceptions to this last rule are as follows: h does not count as a consonant; ch, ph, th, and qu count only as single consonants; and when a stop (p, b, c, g, d, t) is followed by a liquid (1, r), the syllable may be treated as either long or short according to the requirements of the meter ($$$$pat$$$$$ria or patria). In poetry the two-consonant rule also holds when the final syllable of a word within (not at the end of) a verse ends with a consonant and the next word begins with a consonant (e$$$$nim$$$$$ pater).

$$$—macrons indicating long vowels are provided in the Vocabulary at the end of this book), or a diphthong (ae, oe, ei, ui, au, eu; e.g., $$$$saep$$$$e), or a short vowel followed by two or more consonants or the double consonant x (e.g., $$$$quan$$$$tus). Exceptions to this last rule are as follows: h does not count as a consonant; ch, ph, th, and qu count only as single consonants; and when a stop (p, b, c, g, d, t) is followed by a liquid (1, r), the syllable may be treated as either long or short according to the requirements of the meter ($$$$pat$$$$$ria or patria). In poetry the two-consonant rule also holds when the final syllable of a word within (not at the end of) a verse ends with a consonant and the next word begins with a consonant (e$$$$nim$$$$$ pater).

When a word ends with a vowel (or diphthong) or a vowel + -m and the following word begins with a vowel/diphthong or h- + a vowel/diphthong, the two syllables involved were generally “elided,” i.e., reduced to a single syllable, usually with the vowel in the first syllable muted or dropped altogether and the quantity of the second syllable determining the quantity of the resultant single syllable. For example, quantum erat (“Pyramus,” 74) was pronounced quant’ erat and the resultant elided syllable (t’e) is short, whereas foribusque excedere (“Pyramus,” 85) would be pronounced foribusqu’ excedere and the elided syllable ($$$$qu’ex$$$$$) is long.

In the context of this discussion, it should be recalled that initial i-followed by a vowel functions as a consonant with the sound of y, and thus prevents elision (quoque iure, “Pyramus,” 60, is not elided) and can make a preceding syllable long ($$$$et$$$$$ iacuit, “Pyramus,” 121). Likewise intervocalic -i- serves both as a vowel producing a diphthong with the preceding vowel, and as a consonant; e.g., huius is scanned as if spelled “hui-yus.”

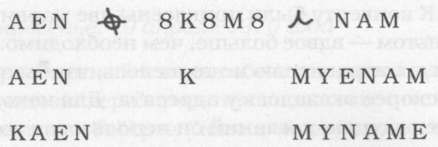

Dactylic hexameter: The dactylic hexameter line consists of six measures, or feet, with the basic pattern of the first five feet being a dactyl, i.e., a long syllable followed by two shorts (—uu). A spondee (two long syllables, — —) is often substituted for a dactyl in the first four feet of the line, rarely in the fifth (a line with a fifth-foot spondee is in fact called a “spondaic line”—see “Midas,” line 93), and the sixth foot is always a spondee (or a trochee [—u], which here has the force of a spondee, due to the slight pause naturally occurring at the end of the verse). The pattern of dactyls and possible spondees may be thus schematized:

An author may vary the balance of dactyls and spondees in a line to achieve some special effect, using more dactyls to describe rapid actions (e.g., “Pyramus,” line 92, where the opening series of dactyls suggests the quick coming of nightfall) or more spondees to describe some slow, or deliberate, or solemn action (e.g., “Pyramus,” 62, where the heavy spondees emphasize the unwavering intensity of the lovers’ passion). Each foot in a dactylic hexameter line begins with a long syllable, and in reading aloud this syllable should be pronounced with a slight stress accent, known as an “ictus,” which may or may not coincide with the normal word accent; poets sometimes manipulate the coincidence or “conflict” (non-coincidence) of ictus and accent for special effect, coincidence producing a smoother, more rapid flow, and conflict creating a harsher, staccato rhythm.

Each line generally contains a principal pause, sometimes two, generally coinciding with the end of some sense unit such as a phrase or a clause; if the principal pause occurs within a foot, it is called a “caesura,” and if it occurs at the division between two feet (which is less common), it is called a “diaeresis.” The commonest pattern in dactylic hexameter involves a major caesura in the third foot, though occasionally there are two equivalent caesurae in the second and fourth feet (marking off some phrase within the line), and there are other patterns as well, thus producing greater rhythmical variety.

Scansion: Scansion is the process of marking the long and short syllables in a line of verse and indicating the feet and the principal pause(s), while keeping in mind the several points made in the preceding discussion. Conventionally, long syllables are indicated with a line over the syllable (—), short syllables with a micron (u); the individual feet are marked off with a slash (/), and the principal pause(s) with a double slash (//). Elisions are marked with parentheses, and the mark indicating the long or short quantity of the resultant single syllable is placed above the space between the two elided syllables.

With practice, students can scan lines with ease, from beginning to end, as the procedure is quite straightforward. But beginners may wish at first to follow these steps: 1) mark all elisions; 2) mark the last two syllables long, as the sixth foot may always be treated as a spondee; 3) mark all syllables long that contain a diphthong or what you know to be a long vowel; then 4) mark all remaining syllables, keeping in mind that the first syllable of each foot must be long, that the fifth foot is nearly always a dactyl, and that, whenever you identify a short syllable in the first five feet, there must always be a second short syllable adjacent to it. Consider the following examples, all drawn from the story of “Pyramus and Thisbe”:

Reading aloud: Scansion is merely a mechanical procedure designed to familiarize students with meter. Once you have had sufficient practice with scanning lines and then reading them aloud, you will find it a fairly easy matter to recite a text rhythmically without needing to scan the lines first. Let me repeat the cardinal rule stated earlier in this introduction: in order to properly recite a text, you need only read the words correctly and think about what they mean. The poet has done most of the work for you, after all, by arranging the words in each verse with the appropriate alternation of long and short syllables; if you simply pronounce each word according to the rules you learned in beginning Latin and have practiced ever since, you will hear and even feel the quantitative rhythms the author has built into the line. Remembering that in the ancient world poetry was performance, you should read aloud yourself as if you were reading a story to a receptive audience; read expressively, with attention to meaning, pausing just briefly at the appropriate points, usually at the end of a phrase or clause (without any exaggerated pause at the end of a line, especially where there is enjambement), and adding the slight verse accent, or ictus, to the first syllable in each foot.

Whenever you pick up a Latin text—whether prose or verse, in fact—read it aloud. Then, once you have read, and translated, and thought about, and discussed a passage in class, and before you pack up your books, read that passage aloud again; as a consequence you will come to appreciate more fully not only the matter of an author’s text but also the manner, often sonorous and dramatic, in which he expected his audience to experience it.