aristocrats and middle-class intellectuals. h at is how the Bolsheviks, a

small sect of revolutionary intellectuals-idealists, suddenly found themselves in charge of a populace ranging from illiterate Russian and Moslem peasants to the Stone Age hunters and gatherers of Siberia. 5 To railroad Marxism and Communism into this “heart of darkness,” the Bolsheviks not only relied on force but also had to customize their ideas to peasant and tribal cultures.

To woo the Asians living on the eastern periphery of the former Russian Empire and beyond, Comintern set up a special Eastern Division in 1919. A year later in Siberia, driven by the same goal, a seasoned and talented Bolshevik organizer, Boris Shumatsky, established a parallel structure, the Eastern Secretariat, to spearhead the Communist gospel in northern and Inner Asia. h e Moscow and Siberian organizations soon merged.

Figure 5.1. Boris Shumatsky (standing, seventh from let ), a polyglot Bolshevik organizer, with his indigenous fellow travelers who railroaded the Communist prophecy in Mongolia. Standing, third from let , is Elbek-Dorji Rinchino, the i rst Red dictator of Mongolia; c. 1921.

Shumatsky was the ideal man for this task. First of all, his revolutionary credentials were impeccable. Unlike many revolutionary leaders such as Lenin, Trotsky, Chicherin, and Bokii, who had middle-class and 106

P R O P H E C I E S D R A P E D I N R E D

bourgeois backgrounds, Shumatsky was a self-taught worker intellectual—a poster proletarian of Marxist propaganda. A railroad mechanic by profession, he had inherited from his Jewish parents a love for books and learning. He also spent many years in the Marxist underground, printing revolutionary l yers, leading workers’ strikes, and of course doing time in prison. Yet his most important asset was his languages.

Growing up in Siberia and rubbing shoulders with indigenous children in the Trans-Baikal area, he learned to speak l uent Buryat in addition to his home-spoken Yiddish and Russian. h is frontier Bolshevik could

easily mingle with the Buryat and the closely related Mongols.

h e i rst major attempt to rally Bolshevik sympathizers from the Eastern periphery was made in 1921, when over a thousand nationalist activists from Moslem and Buddhist areas were brought to Russia to listen to the gospel of revolution. Grigory Zinoviev, a demagogue with a love for superlatives, worked up this crowd by calling for a holy war against the British imperialism (which some of his listeners took literally). Karl Radek, a Polish Jewish intellectual and Comintern leader, invoked the spirit of Genghis Khan, inciting the Asian fellow travelers to storm into Europe and help cleanse it from capitalist mold. h e Comintern bosses excited their listeners to such an extent that many of them began to shout, “We swear!” simultaneously brandishing their sabers and revolvers. 6

A brief romance of Red Russia with Tibetan Buddhism in the 1920s was part of these ef orts to woo Eastern masses to the Bolshevik side.

Historian Emanuel Sarkisyanz explored in detail how Bolsheviks linked their prophecy to messianic expectations of the Eastern populace. He was the i rst to note that, to anchor themselves in Tibetan Buddhist areas, Red Russia and her indigenous allies plugged into such popular local prophecies as Shambhala, Geser, Oirot, and Amursana. In fact, as early as the 1920s, Alexandra David-Neel, the i rst Western woman to go native Tibetan Buddhist, noted with amazement that bits and pieces of the faraway Bolshevik gospel had somehow trickled down into Tibetan oral culture. Moreover, several lamas she talked to identii ed 107

C H A P T E R F I V E

Shambhala with Red Russia. h ey also argued that Geser Khan, an epic hero-redeemer from Tibetan, Mongolian, and Buryat folklore, was already reborn in Russia and ready for action. 7

While persecuting Russian Orthodox Christianity, the major ideological enemy of the Bolsheviks, Lenin and his comrades did not at i rst assault Tibetan Buddhism, which was treated as a religion of formerly oppressed people. In August 1919, the Bolsheviks even sponsored an exhibition of Buddhist art, a revolutionary act that simultaneously attacked Christianity and reached out to Buddhists. Introducing the exhibit, Sergei Oldenburg, the chief administrator of Russian/Soviet humanities at that time, linked Tibetan Buddhism to Communism by saying that Buddha’s teaching had promoted the brotherhood of nations and would certainly help advance the Communist cause in Asia. 8

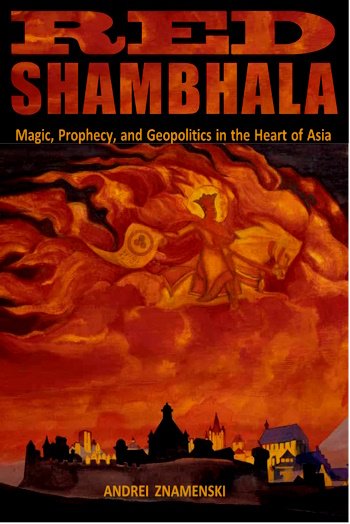

h e chief spearhead of the dialogue between the Bolsheviks and Tibetan Buddhism was the Buryat monk Agvan Dorzhiev (1858–1938). At the very end of the nineteenth century, this prominent Buddhist served as the chief tutor of the thirteenth Dalai Lama, then a young adult.

In the early 1900s, Dorzhiev became His Holiness’s ambassador to the court of the Russian tsar. An ardent advocate of the unity of all Tibetan Buddhist people, Dorzhiev concluded that faraway Russia did not represent a threat to Tibet and could be easily manipulated against China and England to protect the sovereignty of the Forbidden Kingdom.

h e Buryat lama began to spread word among his fellow believers and in the St. Petersburg court that the Russian Empire was destined to become the legendary northern Shambhala and that the Russia tsar was in fact the reincarnate Shambhala king who would come and save Tibetan Buddhists from advances by the Chinese and English. In his dreams, Dorzhiev began to picture a vast pan-Buddhist state under the protection of the tsar and stretching from Siberia to the Himalayas.

Russian monarchs were certainly l attered by these divine references, but they were not too eager to extend their patronage so far southward in fear of antagonizing the English. When in the 1890s Emperor Alexander III read about the project of expanding Russian inl uence into 108

P R O P H E C I E S D R A P E D I N R E D

Figure 5.2. Agvan Dorzhiev in his Buddhist Kalachakra temple in St. Petersburg.

Inner Asia by using the Shambhala prophecy, he remarked in the mar-gins, “All this is so new, so unusual and fantastic, that it is dii cult to believe in its success.” 9

Moscow’s Liberation Theology:

Political Flirtation With Tibetan Buddhism Unlike the tsars, the early Bolsheviks, who lived by the maxim “We are born to make a fairy tale into reality,” never thought it was too fantastic to use popular lore to promote their agenda. So they eagerly plugged themselves into existing Buddhist prophecies, eventually benei ting from some of them. Red Russia inherited Dorzhiev from the old regime as the Tibetan ambassador and was glad to use him to reach out to 109

C H A P T E R F I V E

the Tibetan Buddhist masses. Dorzhiev was at i rst equally enthusiastic about working with the Communists. Although later he became frustrated with them, for a short while in the early 1920s he tied his geopolitical dreams to the advancement of Red Russia’s interests in Mongolia and Tibet.

h is Buryat lama did not approve of the luxurious lifestyle and elitism of some of his fellow Buddhists and also hoped to use the advent of Communism to humble the rich and privileged in monastic communities. Driven by this noble goal, Dorzhiev launched a religious reform among the Buddhist clergy in Siberia, advertising it as a return to the original teaching of Buddha and as a way to maintain a dialogue with the Bolsheviks. In fact, he went quite far, trying to remodel Tibetan Buddhism in Russia according to Communist principles. h e Buddhist

congresses he organized to promote his reform split the faithful into progressives and conservatives. In progressive monasteries that accepted Dorzhiev’s norms, all private possessions were coni scated and turned into collective assets. Clergy ranks were also eliminated, and all monks were obligated to perform productive labor. Instead of silk (a symbol of luxury), monks’ robes were to be manufactured from simple fabric—

an ef ort designed to draw the clergy closer to the masses. Moreover, to eradicate elitism followers of Dorzhiev dropped the veneration of monks who were considered reincarnations. 10 h e chief goal, as Dorzhiev spelled out, was “to cleanse monasteries of all lazy bums and free-loaders, who have nothing to do with Buddha’s teaching.” 11

Bolshevik authorities, particularly the secret police, welcomed these ef orts, which in fact replicated the oi cial reform movement the Bolsheviks themselves pursued in the 1920s in their relations with all de-nominations. h eir long-term goal was to split Christians, Judaists, Moslems, and Buddhists into rival groups and gradually phase them out. 12 A lingering problem for the Bolsheviks working in Tibetan Buddhist areas was a chronic lack of literate people that they could use to do propaganda work and promote the Communist cause. Laboring folk—common nomads and shepherds—were certainly comrades 110

P R O P H E C I E S D R A P E D I N R E D

through and through, but they were all too illiterate to be used as an intellectual resource. h at was how the Bolsheviks and their fellow travelers decided to gamble on low-ranking monks, many of whom had at least an elementary education. Viewed by the Bolsheviks as oppressed by the elite of Buddhist monasteries, junior monks could be well incorporated into the Marxist scheme as wretched of the earth with a good revolutionary potential.

Given that the number of monks in the world of Tibetan Buddhism reached 30 percent of the male population, they were not a small force.

One of Chicherin’s diplomats, a future Soviet ambassador to Mongolia, once remarked, “h is is a formidable force, and it is so formidable that even monks themselves do not quite realize it.” 13 In all fairness, the Bolshevik strategy to woo low-ranking lamas to their side was not totally l awed. In Tibetan Buddhist monasteries people were not equal, and there was a large class of disgruntled monks whose discontent could grow if properly stimulated. h

ere were rich monks who owned vast

estates and cattle and lived in private cells, receiving better food. At the same time, most of the clergy remained humble temple servants throughout their lives, apprenticing with and serving the privileged ones. 14 If circumstances were right, the grudge some of these people might have harbored against their well-to-do brethren could be converted into a rebellion. In the 1920s, Bolsheviks successfully instigated such class warfare in Mongolia, where many low-ranking lamas empowered themselves by joining the ranks of revolutionary bureaucracy and then harassing the ones who stayed loyal to their monastic communities.

h e spearhead of the Communist advance in Inner Asia was Bolshevik indigenous fellow travelers from the Buryat and Kalmyk, two Tibetan Buddhists groups residing within the former Russian Empire.

h e Buryat, an of shoot of the Mongols, lived in southern Siberia on the Russian-Mongolian border. h e Kalmyk, splinters of the glorious Oirot nomadic confederation who escaped from Chinese genocide to Russia in the 1600s, settled northeast of the Caspian Sea in the area where Asia meets Europe. Many Buryat and Kalmyk lamas routinely apprenticed 111