C H A P T E R F I V E

in Mongol and Tibetan monasteries and frequented Lhasa on religious pilgrimages. Since the 1700s, tsars incorporated many males from these two borderland groups into the ranks of the Cossacks. h is paramilitary class was specially formed from former runaway Russian serfs and non-Russian nationalities residing on southern and eastern borders to protect the frontiers of the empire. Since most Kalmyk and Buryat spoke at least basic Russian, they served as convenient middlemen, building cultural bridges between Russia and the Buddhist populace of Inner Asia.

In the early 1900s, several dozens of these indigenous folk were able to graduate from Russian universities, where they were injected with popular ideas of socialism, anarchism, Marxism, and Siberian autonomy.

Figure 5.3. Buryat pilgrims en route from Siberia to Mongolia. h e Buryat, Tibetan Buddhist people from Siberia, were used by the Bolsheviks as middlemen to propagate the Communist liberation prophecy in Inner Asia.

In 1919, writer Anton Amur-Sanan and teacher Arashi Chapchaev, two Kalmyk intellectuals who joined the Bolshevik cause, wrote directly to Lenin suggesting their kinfolk be used to advance Communism among the “Mongol-Buddhist tribes.” Particularly, they came up with 112

P R O P H E C I E S D R A P E D I N R E D

an attractive project to send to the Tibetan-Indian border an armed Red Army cavalry unit staf ed with Kalmyk disguised as Buddhist pilgrims. h e goal was to raise havoc in the very backyard of British imperialism. Lenin was very enthusiastic about this idea but had to put it on hold because the unfolding Civil War temporarily cut European Russia of from Siberia and Inner Asia. 15 h is cavalier scheme rel ected well the revolutionary idealism of the early Bolsheviks, who aspired to liberate the whole earth and lived in expectation of global revolutionary Armageddon that would cleanse the world from the rich oppressors and transport the poor into an earthly paradise. In fact, the same year, Red Army commander-in-chief Trotsky suggested that a Red Army cavalry corps be formed in the Ural Mountains and thrown into India and Afghanistan against Britain. In the Bolsheviks’ geopolitical plans, Central Asia and Tibetan Buddhist areas played an auxiliary role, designated to become highways to carry revolutionary ideas into India, crown jewel of English imperialism.

At the same time, despite their idealism, the Bolsheviks were apprehensive about building large anticolonial alliances involving people of the same religion and the same language family. It was one thing to call the Eastern folk to unite in a holy war against the West; it was a totally dif erent thing to handle large and motley coalitions that could be easily hijacked by enemies and turned against Red Russia. h is explained the Bolsheviks’ uneasiness about and even fear of such supranational units as pan-Mongolism, pan-Turkism, and pan-Buddhism. While working to anchor themselves in Asia, they were ready to tolerate such coalitions for a short while as an unavoidable evil. But as a permanent solution they were totally unacceptable.

For example, when in 1923 Red leaders of Tuva suggested to the neighboring Oirot Autonomous Region in the Altai that they merge into a united Soviet republic, the Moscow authorities were furious. 16

Paranoid about the specter of pan-Turkism, they placed the Tuvan fellow travelers who initiated this scheme on the secret police close-watch list. h e Bolshevik leaders were equally mad the following year when 113

C H A P T E R F I V E

several Tuvan revolutionary leaders suggested they join Red Mongolia.

At er all, before the collapse of the Chinese Empire in 1911, Tuva was formally part of Mongolia. A similar paranoia about pan-Mongolism drove Khoren Petrosian, deputy chief of the Eastern Division of OGPU, to treat with suspicion the attempts of Red Mongols to enlarge their state—a project advocated by Elbek-Dorji Rinchino, a Buryat socialist intellectual who ruled Mongolia as a dictator on behalf of his Moscow patrons. In 1924, this Bolshevik fellow traveler with large revolutionary ambitions speculated that at er his country became totally Communist it should absorb the Buryat in Siberia and merge into a larger Soviet republic, with Tibet to be added later, upon conquest. h e ultimate result would be the emergence of a vast Mongol-Tibetan Communist state allied with Red Russia. Petrosian called this idea very dangerous, fearing that “reactionary forces in Buddhism” could easily use this large state against Red Russia. 17 Rinchino, who did admit that pan-Mongolism might be a double-edged sword, nevertheless stressed, “In our hands, the all-Mongol national idea could be a powerful and sharp revolutionary weapon. Under no circumstances are we going to surrender this weapon into the hands of Mongol feudal lords, Japanese militarists, and Russian bandits like Baron Ungern.” 18

Bolshevik Affi rmative-Action Empire Petrosian’s concerns notwithstanding, grand and ambitious pan-Mongol and pan-Buddhist projects such as Rinchino’s were l awed anyway. h ey were mostly products of indigenous intellectuals’ mind games. Ordinary people did not care about them whatsoever, if they heard about them at all. At er the fall of the Chinese and Russians empires, local and ethnic concerns were dearer to the hearts of the Mongols, Tibetans, Buryat, Tuvans, and Oirot. Not without dii culty, the Bolsheviks understood that and learned how to exploit this reality to their own benei t. But some Bolshevik fellow travelers and also their enemies simply could not get it. For example, i ghting for “united and indivisible”

114

P R O P H E C I E S D R A P E D I N R E D

Russia, the White counterrevolutionaries opposing the Bolsheviks had no room for local ethnic and national sentiments of non-Russians and sought to suppress these feelings. In Siberia, the charismatic admiral Alexander Kolchak, who joined the White cause in 1918, crushed independence movements in the Altai Mountain and Trans-Baikal area by throwing their leaders into prison. Even in those rare instances, as in the case of Baron von Ungern-Sternberg, when the White cause temporarily matched that of indigenous people, the Whites did not tap local nationalisms as a resource. h e same situation existed in China, where, in the at ermath of the revolution, local warlords fought against Mongol and Tibetan sovereignty, trying to crush them and bring them back to China. h

us, in 1919, the Chinese reoccupied Mongolia and eliminated its sovereignty, which stirred the national liberation movement among the nomads.

In contrast, the Bolsheviks began to massage indigenous nationalism, not out of love for multiculturalism but out of necessity. At er all, the Reds were cosmopolitan and urban people who dreamed about building a working people’s paradise without borders, religions, and national loyalties. At the same time, they were a practical gang who knew well that if they wanted to succeed they had to bend temporarily to ethnic and national sentiments. Moreover, the Bolsheviks realized they could use these feelings to their own advantage. Nikolai Bukharin, a prominent Bolshevik theoretician in the 1920s, was very explicit about the opportunity presented by nationalism, which he called “water for our mill”: “If we propose the solution of the right of self-determination for the colonies, the Hottentots, the Negroes, the Indians, etc., we lose nothing by it. On the contrary, we gain, for the national gain as a whole will damage foreign imperialism.” 19

On the Marxist evolutionary scale of human development, nationalism was an unavoidable evil that all people had to go through before they merged into a global commonwealth of brothers and sisters. h e

remedy that Lenin and his comrades of ered to deal with this natural evil was not devoid of logic. If nationalist feelings were surfacing all 115

C H A P T E R F I V E

over the world anyway, let these sentiments l ourish and exhaust themselves on their own instead of i ghting budding nations and nationalities, which would only make things worse. Let them enjoy their folk cultures and languages, and give them their own indigenous bosses to make people happy. h e early Bolsheviks assumed that such lenient attitudes to nationalism would surely help to merge humans into a global cosmopolitan commonwealth—which they assumed was the natural direction the whole world was moving toward. In the 1920s, Joseph Stalin declared, “We are undertaking the maximum development of national culture, so that it will exhaust itself completely and thereby create the base for the organization of international socialist culture.” 20

Ironically, as early as 1917 this would-be dictator, who would preside over one of the most brutal dictatorships in history, was put in charge of the National Commissariat for Nationalities Af airs, a special bureaucratic structure created by the Bolsheviks to draw non-Russians to their side.

In this nationalities scheme of the early Bolsheviks, the Russian population, which was held responsible for the sins of the old tsarist empire, was expected to humble itself and make room for non-Russians to even the social playing i eld. Formerly disadvantaged nationalities were to receive resources and more participation in Communist bureaucracy, government, and education. Simultaneously, in order to empower the less fortunate ones, Marxist historians began to rewrite history, turning indigenous historical characters into heroes, while their Russian counterparts were recast as villains. h at is how the famous Bolshevik

“ai rmative-action empire” was born. Besides the noble goal of making all nationalities equal, courting local nationalist sentiments was a very handy tool of control. Essentially, it boiled down to the good old principle, divide and rule. h is explains why in the 1920s the Bolsheviks tried to create a number of autonomies with their own languages, cultures, and Communist elites. Even miniscule tribes of hunters and gatherers in Siberia, some numbering less than two thousand people, were entitled to their schools, languages, and indigenous bureaucrats.

116

P R O P H E C I E S D R A P E D I N R E D

In the 1920s, the Buryat, Kalmyk, Tuvans, Oirot, Mongols and many other groups received their own autonomies under supervision of the Bolsheviks. In 1921, Red Russia recognized the sovereignty of Mongolia, which formally was still considered part of China. h en in 1923

the Buryat-Mongol Autonomous Soviet Republic was created in Siberia, thereby splitting the Buryat and Mongols apart and casting aside the pan-Mongol dream of building up a great state for all people of Mongol stock. Later, a similar tactic was applied to Tuva, which was made a separate state with its own written language and Bolshevik-friendly indigenous elite. 21 h e assumption was that it was safer to grant Tuva nationhood under Russian supervision than to merge it with Red Mongolia. Overall, the nationalities polices were one of the biggest coups of the Bolsheviks. Even though this strategy later backi red—in the early 1930s Stalin realized that nationalism did not want to exhaust itself, and therefore he had to wipe out indigenous elites and mute the ai rmative

action—in the 1920s, it did allow the Bolsheviks to draw non-Russian nationalities to their side.

Against the Grain: White Baron von Ungern-Sternberg h e success the early Bolsheviks enjoyed in hijacking ethnic and national sentiments becomes visible if contrasted with the failure of the pan-Asian project advocated by Baron von Ungern-Sternberg, a White general with occult leanings who briel y ruled Mongolia in 1920–21.

Too much has been written both in English and Russian about this colorful baron and his sadistic deeds for me to go over it again here. 22

What is more interesting to explore is why he was initially so stunning-ly successful in winning over Mongolia and then failed so miserably by losing it in a few months.

h e collapse of the imperial dynasty in Russia in 1917 and the advent of Communism was a personal tragedy for this psychotic Cossack platoon leader. His whole world was turned upside down. Like many of his Baltic German countrymen who were part of the old Russian imperial 117

C H A P T E R F I V E

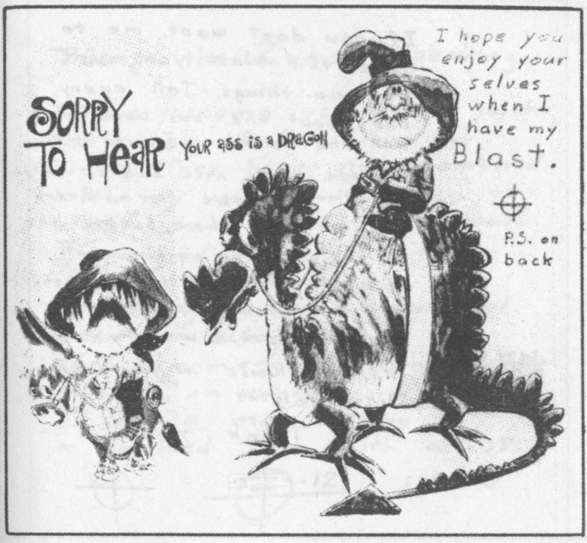

Figure 5.4. “Mad Baron” Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, an occultist and runaway White Russian warlord from Siberia who briel y took over Mongolia in 1920–21.

118