C H A P T E R S I X

Figure 6.3. Commissar for Foreign Af airs Georgy Chicherin (r.), who worked hard to woo Asians to the Bolshevik side, is shown wearing a Mongol robe during a reception for Mongol delegates.

Returning from Moscow, he ordered the revolutionary young Turks to hold on. Everyone was surprised. How could he leave Mongolia defenseless when Ungern, the mad White baron, was ready to roll into and take over the country? Wait and see, was Shumatsky’s answer. h is

turned out to be a brilliant strategy. Shumatsky correctly assumed that by i ghting each other Ungern’s Whites and the Chinese would weaken themselves, and Mongolia would fall into the hands of Red Russia like a ripe fruit. His plan would work better than he expected.

Ungern’s suicidal plans to restore the Chinese monarchy and to drag Mongolia into a war with Bolshevik Russia soon alienated the Mongols, and they turned away from the White general. h e Bolsheviks quickly 134

R E D P R O P H E C Y O N T H E M A R C H

jumped in to encourage Mongol nationalism and help get rid of the

“homeless Russians,” the name the nomads gave to the émigré White Russians. In the meantime, Mongol soldiers who originally sided with the baron began to talk openly about switching sides and joining the Red Mongols. Bodo, Choibalsan, Danzan, Sukhe-Bator, and twenty other radical nationalists who had already been attracted to the message of national and social liberation coming from Moscow gathered in the borderland town of Kiahta. h

ere, groomed by Borisov, Rinchino, and

other Comintern agents, they were able to raise a small army of i ve hundred nomadic warriors. h is indigenous detachment, the nucleus of the future Red Mongol army, embodied the Comintern strategy of “using Mongol national feelings for the defense of Mongol independence under the l ag of a Mongol army.” To give additional stimulus to the revolutionary spirit of this ragtag crowd of shepherds, drit ers, and junior lamas, Borisov gave them food, warm underwear, and tobacco. 4 Simultaneously, assisted by Choibalsan and Sukhe-Bator, he worked hard to organize those who had at least some elementary education into the Mongol People’s Revolutionary Party (MPRP). Beefed up by Buryat and Kalmyk revolutionaries imported from Siberia, MPRP was to become a Comintern tentacle ensuring that the nomadic masses were moving in the correct direction.

h e Bolsheviks’ plans proceeded smoothly. h e Red Mongols’ ef orts received a handy theological back up when, at the end of 1920, Gutembe, a prominent lama oracle, conveniently went into a trance and came up with a prophecy that the Mongol state needed urgent help from outside.

Comintern folk became so excited that they dispatched three Mongol agents to coni rm the prophecy and to secure its power for the Red cause. Gutembe turned out to be very helpful, informing the visiting revolutionaries that just before their arrival one of the avenging gods had entered his body, told him how rotten the present state of society was, and also issued guidelines. As a special favor for the Red Mongols, the oracle went into trance again to ask the god more questions. Lighting his oil lamp and incense, reciting a ritual text, and brandishing a 135

C H A P T E R S I X

sword, he began raving and foaming from the mouth. At er an assistant poured a glass of vodka into his mouth, the oracle relaxed a little and assured the Red Mongols that soon they would succeed. 5

Meanwhile, Borisov was moving back and forth cementing and equipping the Red Mongols gathering on the Russian-Mongolian border ready for action. In 1921, the operational budget of the Mongol-Tibetan Section, which became the headquarters of the Mongol revolution, reached $112,000 Mexican dollars. 6 Of this amount, the major bulk ($100,000) was spent to acquire weapons and supplies for the Mongol revolution.

Borisov himself delivered much of this cargo in a caravan that reached the border in February of 1921. In addition, the Oirot revolutionary oi cially set aside $6,000 for bribes to be paid to various Mongol and Chinese headmen to smooth i eld trips of Comintern agents through Mongolia. Borisov neatly called it a special “engagement and counterintelligence fund” for “materials payments and git s to people who are not yet revolutionized by our propaganda.” 7 Bringing the Red Shambhala kingdom to Mongolia was not a cheap business.

The Triumph of Red Shambhala in Mongolia On June 22, 1921, when Ungern was defeated and captured, the small Mongol army, mainly Buryats and Kalmyks was already marching deep into Mongol territory. h e arrival of the Red Mongol troops in Urga on July 7, 1921, was announced by the piercing sounds of trumpeters marching in front, blowing into traditional Buddhist shells. h e trumpeters were followed by the Mongol cavalry in two lines. h e squadron on the let rode with a red banner, while the one on the right carried a yellow banner. To nomadic revolutionaries the whole scene was very symbolic. h e red banner stood for the rivers of blood they spilled in the cause of national liberation, which would eventually lead people to the “golden age kingdom,” symbolized by the yellow. 8 h e ceremony culminated in the ritual sacrii ce of a White oi cer named Filimonov, chief of Ungern’s counterintelligence service, to one of the avenging 136

R E D P R O P H E C Y O N T H E M A R C H

god-protectors of the Buddhist faith. His blood was used to smear the banners of the Red Mongols—an ancient ritual to appease the wrathful gods and secure new victories. 9

h e Shambhala army was coming again from the north, just as the legend said. Only now it was Red Shambhala. It was now time to engage old prophecies. Choibalsan, Sukhe-Bator, and rank-and-i le Red Mongols were happy to portray the victory as a triumph of the prophetic Shambhala kingdom. In fact, when the i ve hundred nomadic warriors were waiting on the Russian-Mongolian border before the attack, they put together a song, “h e War of Northern Shambhala,” calling Mongol soldiers to rise up in a holy war against aliens, particularly the Chinese. One of the lines went, “Let us all die in this war and be reborn as warriors of Shambhala.” 10 h e nomadic warriors were convinced that if they participated in the sacred war they would be able to liberate themselves from samsara (the cycle of reincarnations) and end up in the happy Shambhala dreamland.

Figure 6.4. “Red lama” commissar of new Mongolia with his scribe, 1928. Note the sacred tanka scroll in the background with the face of Lenin, which replaced Maitreya and other Buddhist deities in the new Mongol iconography.

137

C H A P T E R S I X

In the early 1920s, not only Shambhala but the entire Buddhist faith and existing prophecies were used by the Red Mongols to entrench themselves among the populace. For a while, Communism linked to Buddhism was advertized as some sort of Bolshevik liberation theol-ogy customized for common shepherds and lamas. Until at least 1928, Choibalsan, Rinchino, Sukhe-Bator, and their comrades deliberately tied their political and social reforms to messianic and prophetic sentiments popular among Inner Asian nomads. 11 Moreover, the political system of Red Mongolia briel y became a strange hybrid of Communism and Buddhism. In this Red theocracy, the Bogdo-gegen acted as the formal head of the country, while the government was run by Bolshevik fellow travelers, many of whom themselves came from the ranks of Buddhist clerics.

A major headache for the new Red Mongol regime was that the western part of their country was only loosely connected to Urga. h ere the

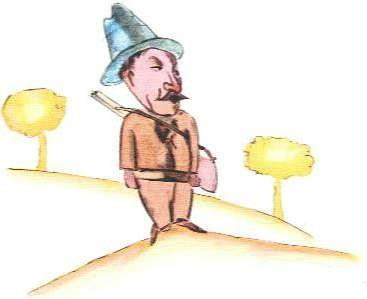

notorious Ja-Lama, who had returned to “his people” in 1917 from his exile in Russia, was still running wild and free. h e Avenging Lama and self-proclaimed grandson of the legendary Amursana had gotten a second wind. Ja-Lama held up a rich caravan of i t y Tibetan traders loaded with gold and silver, which gave him startup capital to build Figure 6.5. Remains of Ja-Lama’s magnii cent fortress in the Gobi Desert, 1928.

138

R E D P R O P H E C Y O N T H E M A R C H

another i efdom and to lure supporters. 12 Soon with a small army of three hundred warriors, he settled in a desert area conveniently located near a trading route on the border between Inner and Outer Mongolia.

Following his totalitarian dreams, Ja-Lama was turning this area into an orderly desert oasis, using slave labor of prisoners captured during his raids to erect a magnii cent fortress. Canals and wells were dug, and aqueducts built. A group of Chinese prisoners tended opium i elds, one of Ja-Lama’s major sources of revenue.

At i rst Shumatsky, Borisov, and Rinchino had high hopes for Ja-Lama and thought about making him a guerrilla commander who could help them i nish pockets of White resistance. At one point, the Mongol-Tibetan Section sought “to establish urgently a formal connection with the partisan movement of western Mongolia by sending Dambi-Dzhamtsyn [Ja-Lama] a responsible representative of the [Mongol] people’s party, who would steer this movement ideologically in a correct direction.” 13 h e Bolsheviks even of ered the “lama with a gun”

the oi cial title of a national leader, Commander of Western Mongol Revolutionary Forces, and sent symbolic git s: a Russian military cap and two small hand grenades. 14 Yet the reincarnation of Amursana was not a fool. As a former Russian subject who had rubbed shoulders with Marxist revolutionaries during his Siberian exile, he could easily i gure out the Bolsheviks’ true intentions. Besides, obsessed with a totalitarian dream of his own, Ja-Lama did not want to share power with anybody.

His plan was to set up a large modern theocracy that would unite the Altai, western Mongolia, and western China—areas that had composed the glorious seventeenth-century Oirot confederation. So Ja-Lama l atly rejected the advances of Comintern agents.

Despite all his experience and cunning, the ruthless lama did not know how devious and imaginative his opponents could be. Unable to tame the unfriendly reincarnation, Shumatsky, Borisov, and their Mongol comrades decided to beat “Amursana” on his own spiritual ground by making up their own reincarnation in order to split Ja-Lama’s l ock and confuse local nomads. For the role of Red Amursana, 139

C H A P T E R S I X

the Bolsheviks picked Has Bator, a young lama priest and new convert to the Red Mongol cause, who, at er a short training and indoctrina-tion in Irkutsk, was sent to western Mongolia with two dozen Comintern agents and one thousand Red Mongol and Buryat troops. h e goal of this “military- political expedition,” as Shumatsky labeled it, was to put local anti-White and anti-Chinese guerrilla units under the Comintern wing. 15

Bolsheviks and their Mongol fellow travelers initiated a sophisticated game of image making to bill Has Bator as the new and better reincarnation. h ey made him three luxurious felt tents decorated inside with antique weapons. Simultaneously, word was spread that the real Amursana had i nally come from his northern land. Part of the game was creating an aura of mystery around the newly anointed one. Every day Red Amursana received mysterious packages from somewhere. 16