adhuc: adv., up to this time, still, yet.

rarissimus emptor: the Christians would not eat meat from the pagan temples.

283. actum: here, procedure.

Secunde: in the body of his letters to Pliny, the Emperor Trajan often uses Pliny’s cognomen, as here, sometimes with carissime added.

excutiendis: excutere,to shake out, examine, investigate.

284. Christiani: as Christians.

285. in universum: in general; i.e., there can be no fixed prescription which will cover every single case.

certam:fixed, unvarying.

286. constitui: constituere, to place, establish, determine, decide.

conquirendi non sunt: conquirere,to search out; Trajan intended no aggressive persecution of the Christians. While generally answering Pliny’s initial question regarding the conduct of investigations, the emperor does not give his opinion on the degree of punishment appropriate to the offence (Epistulae 10.96, line 233, quatenus…puniri soleat), thus by silence endorsing the usual penalty of execution.

arguantur: arguere,to make clear, prove; there must be a full trial in court and a formal conviction, not merely an accusation.

287. ita: in such a way (that), with the stipulation (that).

288. re ipsa: in actual fact (lit., by the thing itself), as defined by supplicando.

Pliny is concerned about humanitarian considerations but feels that the “superstition” must be curbed.

Ideo dilata cognitione, ad consulendum te decucurri. Visa est enim mihi res digna consultatione, maxime propter periclitantium numerum. Multi enim omnis aetatis, omnis ordinis, utriusque sexus etiam vocantur in periculum et vocabuntur. 275 Neque civitates tantum, sed vicos etiam atque agros superstitionis istius contagio pervagata est; quae videtur sisti et corrigi posse. Certe satis constat prope iam desolata templa coepisse celebrari, et sacra sollemnia diu intermissa repeti passimque venire victimarum carnem, cuius adhuc rarissimus emptor inveniebatur. 280 Ex quo facile est opinari quae turba hominum emendari possit, si sit paenitentiae locus.

10.97

Trajan replies, probably within a few weeks, to the preceding letter, generally approving Pliny’s procedure, advising against witch-hunts and the acceptance of anonymous accusations, but insisting that Christians who do not renounce their religion, whether or not guilty of any related crime, must indeed be punished.

Traianus Plinio

Actum quem debuisti, mi Secunde, in excutiendis causis eorum qui Christiani ad te delati fuerant, secutus es. Neque 285 enim in universum aliquid, quod quasi certam formam habeat, constitui potest. Conquirendi non sunt; si deferantur et arguantur, puniendi sunt, ita tamen ut qui negaverit se Christianum esse idque re ipsa manifestum fecerit, id est supplicando dis nostris, quamvis suspectus in praeteritum, veniam ex paenitentia 290 impetret. Sine auctore vero propositi libelli in nullo crimine locum habere debent. Nam et pessimi exempli nee nostri saeculi est.

289. in praeteritum: in the past.

291. pessimi exempli: with est, it (i.e., the practice of crediting anonymous accusations) is (of) a very bad precedent; PRED. GEN. OF DESCRIPTION, as also nostri saeculi.

nostri saeculi: lit., of our age = appropriate to our age, i.e., Trajan’s relatively benevolent administration.

Trajan Louvre, Paris, France

Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY.

THE VULGATE

The Old Testament, in origin a collection of Jewish writings composed chiefly in Hebrew, was translated into Greek by several different hands beginning in the third century B.C. According to a popular ancient tradition, the translation was produced for the library of the Egyptian king Ptolemy II Philadelphus by a panel of 70 Jewish scholars, hence the title “the Septuagint” often applied to the work.

During the latter half of the first century of our era the New Testament was composed in Greek. As Christianity spread through the Latin-speaking world, including Italy, Gaul, Spain, and North Africa, anonymous Latin versions of various parts of the Bible, the so-called Vetus Latina, began to appear from the second century onward. By the fourth century the number of translations and variants had become confusing, and the biblical scholar Eusebius Hieronymus (ca. A.D. 347–420), better known as St. Jerome, was commissioned in the early 380’s by Pope Da-masus to produce a standard Latin version. Working at first from the Septuagint and later from the original Hebrew for the Old Testament, and directly from the Greek for the New Testament, Jerome ultimately—over a period of about 25 years—produced the “Vulgate,” the Editio Vulgata of the Bible, so-called from his intention that it serve as a highly readable popular edition for the vulgus, the common people. Jerome’s edition for centuries was the standard Latin text of the Bible and exercised a profound influence on the church and on European thought generally.

Just as the Greek New Testament had been written in the simple language of the common people, the so-called koine, so that it could be easily understood by them, likewise the Vulgate was phrased ad usum vulgi and not in the rich elegant style of Cicero (with which Jerome was highly conversant and which he employed in much of his other writing). While his translations from both the Greek and Hebrew were at times highly literal, at others quite free, the structure of his sentences is nearly always eminently simple, with more coordination than subordination. Among other characteristics of Jerome’s language are the frequent use of quod, quia, or ut with either the indicative or the subjunctive to express indirect statement, the use of prepositional phrases instead of simple cases (e.g., dix.it ad eum = dixit ei), the infinitive to express purpose or result, and the use of new words and of new meanings for old words. Such usages continued and were elaborated throughout medieval Latin and illustrate the process by which vulgar Latin was gradually transformed into the Romance languages.

The readings excerpted for translation in this text include some of the best known and most influential passages from the Bible, among them the Ten Commandments, Job’s views on the inaccessibility of wisdom, Ecclesiastes on the futility of man’s earthly existence, selections from Christ’s “Sermon on the Mount,” and the stories of the “Good Samaritan” and the “Prodigal Son.”

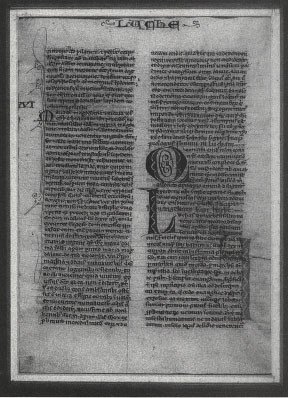

Vellum page from Dominican manuscript of miniature Vulgate bible (Mark 16-Luke 1), ca. 1240 Paris, France

Robert I. Curtis.

1. cunctos: = omnes.

sermones:words, sayings.

4. habebis: the fut. indic, can be used with the force of a command.

coram: prep. + abl., in the presence of.

5. sculptile: a carved thing, statue.

omnem: here (and in 17 below), any.