Dixit autem et ad quosdam, qui in se confidebant tamquam iusti et aspernabantur ceteros, parabolam istam: Duo homines ascenderunt in templum ut orarent, unus Pharisaeus et alter 220 publicanus. Pharisaeus, stans, haec apud se orabat, “Deus, gratias ago tibi, quia non sum sicut ceteri hominum—raptores, iniusti, adulteri, velut etiam hic publicanus. Ieiuno bis in sabbato; decimas do omnium quae possideo.” Et publicanus, a longe stans, nolebat nec oculos ad caelum levare; sed percutiebat pectus 225 suum, dicens, “Deus, propitius esto mihi peccatori.” Dico vobis, descendit hic iustificatus in domum suam ab illo, quia omnis qui se exaltat, humiliabitur, et qui se humiliat, exaltabitur. (Luke 18.9–14)

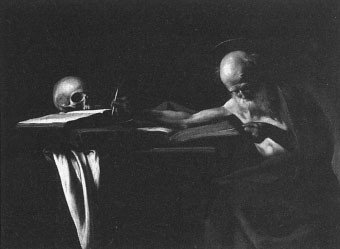

“St. Jerome Writing”

Caravaggio, 17th century

Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy

Scala/Art Resource, NY.

MEDIEVAL LATIN

Although the western Roman empire lapsed into political instability in the fifth century of our era, the influence of Rome persisted, even into our own day of course, and Latin remained the primary language of church literature and much of secular literature throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance of the 14th–16th centuries. Medieval Latin, it should be said at the outset, was by no means merely an anemic or imitative extension of its classical parent. Rather, in its vibrant admixture of classical and vulgar Latin (encountered in the previous unit on Jerome’s Vulgate), the language became the lingua franca of the ecclesiastical world and the intellectual secular world in the fields of literature, including widely various and often innovative forms in prose and poetry, of religion and philosophy, of politics and diplomacy and law, of education, and of science.

A rich variety of style and expression developed over the centuries and in the many different regions of chiefly western and central Europe where the language continued to be used alongside, and often under the influence of, the local vernacular. This variety is well represented by the selections in this book, which span a period of about 600 years, ranging from the Venerable Bede’s accounts in the 8th century of Pope Gregory’s mission in England and the poet Caedmon’s inspired hymns, to the allegorizing “Tale of Three Caskets” (a source for Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice) from the 14th-century Gesta Romanorum. Included also are three songs—one a religious meditation on the vanity of human life, one a sprightly celebration of the return of springtime and young love, and the third a raucous drinking song—from the 13th-century Carmina Burana (made famous by the cantata of the same name first produced by the German composer Carl Orff in 1937), as well as three of the most famous medieval hymns, from the 12th and 13th centuries, Stephen Langton’s reverent Veni, Sancte Spiritus, the profoundly sorrowful Stabat Mater, and Thomas of Celano’s hypnotic prayer on Judgment Day, the Dies Irae, which was early on incorporated as a sequence in the requiem mass and later included in arrangements of the requiem composed by Mozart, Verdi, and others.

Although there were many changes and local variations in vocabulary, orthography, pronunciation, and grammar, medieval Latin remained more stable than one might have expected over the 1,000 years of its history from roughly A.D. 500 to 1500, thanks in particular to its preservation by churchmen in Rome and in monasteries throughout Europe. For the selections presented below, classical spelling has been followed, and the meanings of new words, as well as non-classical meanings for classical words, are provided in the notes. Grammatical differences are also pointed out in the notes, generally at the first occurrence or two; following are the commonest variances from classical Latin to be encountered in the readings (some of them already seen in the preceding selections from the Vulgate and many of them approximating the syntax of modern European languages—a fact that often makes for easier reading and comprehension): briefer, less complex sentences (students will be relieved!); indirect statement introduced by quia, quod, or ut, with either an indicative or subjunctive verb; use of quod to introduce purpose and relative clauses; frequent use of the indicative in place of the subjunctive, and occasionally the opposite; use of debere and habere as auxiliary verbs (indicating, respectively, futurity and obligatory action); use of sum as an auxiliary in so-called “analytical” (periphrastic) verb forms such as eram manens for manebam; increased range of uses for infinitives, e.g., in place of ut + subjunctive; use of non for ne; variance in case uses and gender; frequent use of prepositional phrases in place of simple case uses (e.g., per + accusative instead of ablative of means or de + ablative instead of the prepositionless ablative of description); and non-reflexive use of suus/sui.

Finally, since all these passages, especially the verse selections, should be read aloud, students should note the relatively few major differences between classical and medieval (or ecclesiastical) pronunciation. First, the rules for accent are largely the same; occasionally the accent was shifted to suit a poem’s meter, which was accentual (qualitative) not quantitative, as explained in the notes. The consonants c and g were pronounced soft before the vowels e and i, as in agito (“ajito,” like English “agitate”) and cetera (“chaytera”); v was pronounced as in English, not as a “w” and the diphthongs ae and oe were pronounced as English long “a,” as in quae (“kway”).

1. praetereunda: sc. est.

opinio: here, story.

Gregorio: after living some years in his own monastery in Rome, Gregory (ca. 540–604) was called to be Pope Gregory I in A.D. 590; in 597 he sent to the pagan Anglo-Saxons in England Augustine (the Lesser), who established a monastery at Canterbury and made it the base for missionary work throughout England.

2. quia…multi…confluxissent et…Gregorium…vidisse (5): dicunt is followed by two IND. STATES., one a quia (that) cl. + subjunct. typical of med. Lat. and the other an acc. + inf. construction usual in class. Lat.

3. mercatoribus: mercator, merchant.

venalia:for sale, to be sold.

4. fuissent conlata: = essent conlata.

6. venusti: charming.

7. egregia: unusual, remarkable; note the combination of ABL. OF DESCRIPTION here with the GEN. OF DESCRIPTION in the preceding phrase.

8. dictum…est: impers. pass.

quia: sc. adlati essent.

9. incolae: incola, inhabitant.

aspectus:appearance, aspect; GEN. OF DESCRIPTION.

rursus: or rursum, adv., again.

10. insulani: insulanus, islander; sc. essent.

paganis: lit., belonging to a pagus (village) = rustic, and hence pagan (because the old pre-Christian religion survived longest among the country people).

11. quod: commonly used in med. Lat., like quia (above, line 2), to introduce a subjunct. vb. in IND. STATE.

12. intimo: innermost.

corde: cor,heart.

suspiria: suspirium,sigh.

pro: interj., + voc., oh, ah.

13. lucidi: bright, shining.

tenebrarum: tenebrae, pl., shadows, darkness; with auctor = the Devil.

14. possidet: possidere, to possess.

gratia: here, grace.

frontispicii: frontispicium,exterior, appearance.

15. gestat: gestare, to carry about, have.

16. vocabulum: name.