A lot of Israeli protesters have trouble with their parents. In my twenties I told them I was bisexual, and that was easier than telling them that I was a leftist, or later that I was dating an Arab man. My parents are definitely not supportive of my politics, but they support me, so I can say both sides are making courageous strides at achieving peace. We all make an effort. And I’ve never been injured or spent any real time in jail, so they haven’t had to face that sort of thing yet.

Even though I go to weekly protests, I don’t necessarily think protests are the most effective action. I think boycotts are a lot more useful in terms of leverage on the Israeli government.15 But it’s important for me to meet people face to face and understand what’s going on in the West Bank and make friends. And I think it’s good for forming relationships of trust, based on an agreement that Palestinian rights are being infringed upon.

I FEEL MORE LIKE I CAN BE MYSELF IN RAMALLAH THAN IN TEL AVIV

For years I planned to move to Ramallah. Then I finally did it at the start of 2014. I had a lot of reasons for making the move. For one, my partner is here. And I’m closer now to the protests. I’m learning Arabic, and living in Ramallah really helps me pick it up quickly.

I still go back to Israel every couple weeks, to visit friends in Tel Aviv or to see my family in Omer, because there’s no way they’re coming to visit me here. My brother has a new baby, and everything else pales in comparison to how important it is for me to be in her life as she grows up. I’ll always get a little nervous at checkpoints, because I have a “security record,” but I never have any real problems. And I haven’t had any issues in Ramallah because of my Israeli citizenship. I don’t go around telling everyone I’m Israeli, but I don’t try to hide it either. For the most part, I feel like my life here is completely normal. I go shopping in the market, I’m comfortable in the streets. There are moments here when I’ll meet someone new, maybe with a group of friends, and I’ll talk to them for a while and they’ll think I’m nice. Then I tell them I’m Israeli, and they sort of have to recalibrate a little. But I still feel comfortable here. It’s a little ironic because I’m hiding my identity a bit in Ramallah, but I feel more like I can be myself here than I can in Tel Aviv.

1 Area A territories are administered and policed by the Palestinian Authority. For more information on Areas A, B, and C, see the Glossary, page 304.

2 Mevaseret Zion is a city of 25,000 located six miles west of Jerusalem.

3 The Hatikva is the Israeli national anthem.

4 Omer is a suburb of over 7,000 northeast of Be’er Sheva. Be’er Sheva is a city of over 200,000 south of Jerusalem.

5 Military service starting at age eighteen is compulsory for most Israeli citizens. For more on the Israeli Defense Force, see the Glossary, page 304.

6 The Oslo Accords marked the end of the First Intifada and established a tentative plan for Palestinian governance of the West Bank and Gaza. For more information, see the Glossary, page 304.

7Gadna is short for Gdudei No’ar, or “youth battalions.” The Gadna tradition dates back to before the formation of Israel as a state.

8 Khan Younis is a city of over 250,000 residents in southern Gaza. It’s the second largest city in the Gaza Strip behind Gaza City.

9 The Second Intifada was also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada. It was the first major conflict between Israel and Palestine following the Oslo accords, and it lasted from 2000 to 2005. For more information on the Intifadas, see Appendix I, page 295.

10 Rachel Corrie was an American pro-Palestinian activist who was killed by the Israeli military in Rafah in 2003 during the Second Intifada. She was crushed to death by a bulldozer while trying to defend a Palestinian man’s home from demolition. Tom Hurndall was a British photography student who was shot by an Israeli sniper in Rafah in 2003 (after a nine month coma he died in 2004). James Miller was a British filmmaker who was shot and killed by Israeli military in Rafah in 2003. The story of the three deaths is investigated in the BBC documentary When Killing is Easy (2003).

11 Operation Cast Lead was a military invasion of Gaza from December 2008 to January 2009 in what Israel claims was a response to rocket fire into Israel and the militarization of Hamas. Approximately 1,400 Palestinians were killed during the invasion. For more information, see Appendix I, page 295.

12 Bil’in is a village of around 1,800 people located thirty miles east of Tel Aviv.

13 Levinsky Park is located in south Tel Aviv. The surrounding neighborhood is home to many North African immigrant communities.

14 Palestinian activists often refer to the state of Israel as “’48” as a way to protest the borders claimed by Israel after its declared statehood and subsequent military occupations.

15 The Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement (BDS) is an international campaign to apply political and economic pressure on Israel to end the military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.

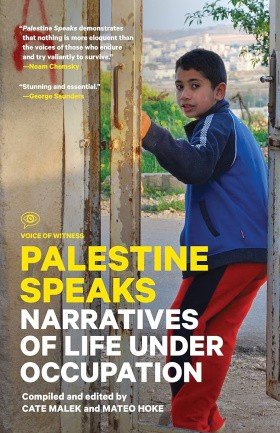

UNRWA MURAL IN RAMALLAH, WEST BANK

KIFAH QATASH

Homemaker, student, 42

Born in Al-Bireh, West Bank

Interviewed in Ramallah, West Bank

Both Kifah Qatash and her sister Hanan love black coffee. Their ritual is to make a big pot and then sit on the overstuffed sofas in Hanan’s living room in Ramallah and talk late into the evening while drinking cup after bitter cup. It is in that same living room and with that same coffee pot that we sit down with Kifah for her interview. She speaks mostly in English, with Hanan translating when she falters.

Kifah was born and raised in the neighboring city of Al-Bireh. Although it is called Ramallah’s twin, Al-Bireh is calm and traditional compared to Ramallah’s crush and bustle. Al-Bireh is a largely Muslim community with elegant nineteenth-century Palestinian houses made of local white limestone. It hosts a sizeable community of refugee families, including Kifah’s family.1 Though now peaceful and sedate, Al-Bireh has not always been so. Kifah lived through the two Intifadas there, which meant years of Israeli soldiers on the streets, imposing curfews and raiding houses. Though she’s built a life in Al-Bireh, Kifah longs to return to Yazur, the village her family fled in 1948, although she has only seen it during a few short visits as a child.

When we meet, Kifah is dressed simply in a black abaya and white head scarf.2 She is quiet but speaks with a clear self-assuredness, and is quick to laugh. Kifah is looked up to as a leader in her community through her years of working on behalf of prisoner rights. She believes that this advocacy work, along with her leadership in a network of Palestinian activists in her mosque, may have brought her to the attention of the Palestinian Authority. The Palestinian Authority is especially concerned about the rise of fundamentalist and Islamist political factions such as Hamas, the party that won elections in the Gaza Strip in 2006 and subsequently drove Fatah—the party that controls the PA—out of Gaza. Kifah believes that information likely passed from the PA to Israeli police led to a raid on her home in 2008, and to her arrest in 2010. She was imprisoned for a year without charges.

I’D WATCH EVERYTHING THROUGH THE WINDOW

My family is originally from Yazur Village,3 but I was born in Al-Bireh.4 I still live in Al-Bireh. It has affected me hugely that I’m not on the land that my family once owned in Yazur. I still want to return to my village someday.

When I was a child, it wasn’t always easy being a refugee in Al-Bireh. On the one hand, people loved us. They saw refugees as an important part of Palestinian history. At the same time, the residents of Al-Bireh were sort of a closed community. A lot of landlords wouldn’t rent to refugees—only to people who were from the town. And in a lot of cases, girls from refugee families had a hard time marrying boys from Al-Bireh families. Those families wouldn’t be interested in having their sons marry refugees. When I was a child, we were actually one of the few refugee families in Al-Bireh. My father had moved here from the refugee camps near Ramallah after he started a carpentry business here. Later, he started a small grocery as well. But refugees were rare then—now we’re more common in Al-Bireh.

Still, Al-Bireh was not a bad place to grown up. It was very quiet. The neighborhood we lived in was peaceful. I was the third child—I had an older sister, older brother, and two younger sisters. My older sister, Hanan, was a year older than me, and we were best friends. We played in the hills nearby, we rode our bikes, climbed trees, played charades. We played with the neighbors. It was safe, and we felt free. We could even stay out at night. My parents wanted to make us feel like we had a normal life. They had grown up in the camps, and life was much harder for them there—especially my father, who is deaf.

When I was a child, I was most aware of the occupation when my family traveled out of Al-Bireh. Travel was difficult. For example, when I was a young child, my family would often visit relatives in Nablus.5 Quite often, we would start our journey to Nablus, and all of a sudden, we’d hit a roadblock set up by Israeli soldiers.6 They’d stop our car and send us back the way we came. So they deprived me of those visits, and that really affected me, especially when I was a child. But I remember visiting the site where Yazur had been. There weren’t any homes there any more—it was an industrial zone. That affected me as well, to see that this place where my grandparents used to have a big home was now a bunch of factories.

From what I remember, there were always Israeli settlers around, though we didn’t have a big settlement near us until 1981. That’s when the Psagot settlement was built up.7 But when I was a child, it didn’t seem like such an exceptional thing. We’d see settlers pass through town because we shared a main road. For the most part, we didn’t worry too much about the settlers or about Israel.

Then, when I was a teenager, the First Intifada started, and things changed rapidly, even in our quiet neighborhood in Al-Bireh.8 Suddenly, we could expect to hear of friends or neighbors who were killed by soldiers. We had to worry that soldiers would come in the middle of the night. When they wanted to find someone, soldiers would break into houses in the middle of the night—sometimes they’d break into everyone’s house in the neighborhood. I was curious, and I’d watch everything through the window. My older sister, she was more afraid, and she said she refused to see young men being humiliated in the street. Sometimes soldiers would arrest men and have them strip down to their underwear in the middle of the road. Sometimes soldiers would laugh at the men, make them sing songs. Our house was on one of the main streets in town, so we had this happening outside our window quite a lot.

Sometimes the soldiers would make every male in the neighborhood come out of their house. I remember my brother being forced into the street, and he was still just a child. For more than a month after the Intifada started, there was a curfew—we couldn’t leave the house even to go to the garden. My father ran a mini-mart on the ground floor of our building, and we were afraid to even go downstairs to get things to eat. We knew if soldiers saw us through the windows, they could do anything—we could be taken. Anyway, that’s what we were afraid of as girls. And it wasn’t just soldiers. Armed settlers from Psagot, men in civilian clothes, would be in the streets as well. Suddenly, we realized just how close Psagot was to us, and just how scary it was to have a settlement so close.

As the Intifada continued over the years, I started to get more involved. I started to go to demonstrations. During that time when demonstrations happened against the occupation, it could seem like everyone dropped what they were doing to join—people would leave work, strike, whatever. The same with students. We’d march out of the classrooms for demonstrations sometimes.

When I was around sixteen, I was at school one day, and we heard about a big demonstration that was happening in town. Many students got up and started walking out of the building to join in. But when we got to the front entrance of the school, a captain from the Israeli army was there blocking the way, trying to lock up the school. He didn’t want us students in the streets.

I filled up a bucket with water, marched up to the captain, and soaked him with it. He got mad. He arrested me and brought me to his jeep. Then he drove around with me handcuffed in the back seat. He said he was going to exile me from Palestine for what I did to him! We drove through Al-Bireh and Ramallah for maybe four hours while he patrolled, and then he took me to the police station where they called my parents. At the time, it was rare for girls to be in demonstrations or out in the streets. When I saw my parents, they told me that friends and neighbors had been calling them all day, saying that they saw me in the back of an Israeli Jeep! It was unusual then to see a female get arrested. I think my parents were probably more scared than I was. I just felt like the Intifada was in my blood. It was my duty to resist.