4 In 2000, there were seventeen Israeli settlements in Gaza and a little over 6,200 settlers.

5 The hijab is a garment that covers the head and neck and is worn by many Muslim women throughout the world.

6 In 2005, Israel announced a unilateral withdrawal plan from the Gaza Strip. For more information, see Appendix I, page 295.

7 The Islamic University of Gaza is an independent university system in Gaza City. It serves just under 20,000 undergraduates.

8 Gilad Shalit was an Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) soldier who was kidnapped in Israel in June 2006 by Gazan militias affiliated with Hamas. He was released as part of a prisoner swap in October 2011.

9 Human Rights Watch is a non-profit organization based in the U.S. that investigates human rights abuses around the world. HRW conducts fact-finding missions with the help of journalists, lawyers, academics, and other experts.

10 The strikes on Gaza in 2008 lasted around three weeks, from December 27, 2008, until a cease-fire on January 18, 2009. The invasion was named Operation Cast Lead by the Israeli military. For more information, see the Glossary, page 295.

11 In January of 2011, millions of protesters throughout Egypt gathered to demand the ouster of Egypt’s president, Hosni Mubarak, who had been in power for three decades.

12 The Rafah border crossing is the sole border crossing from Gaza into Egypt, and since Israel imposed a blockade on Gaza in 2007, the Rafah crossing is often Gazans’ only accessible point of exit from the Gaza Strip. The crossing is often closed as well, however, and since 2007 it is very difficult for Gazans to leave the Gaza Strip.

13 For more information on the Dome of the Rock, see the Glossary, page 304.

14 Operation Pillar of Defense was an eight-day assault by the Israeli military starting November 14, 2012. For more information, see the Glossary, page 304.

15 Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City is the largest medical facility in Gaza.

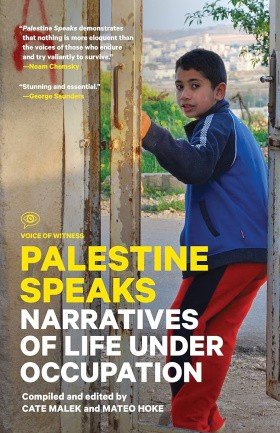

WEST BANK FARMER WITH ISRAELI SETTLEMENT IN BACKGROUND

LAITH AL-HLOU

Farmer, day laborer, 32

Born in Bethlehem, West Bank

Interviewed in the West Bank

The first thing we notice as we drive to Laith Al-Hlou’s home southeast of Bethlehem is the challenge presented by the roads. Some roads are almost too steep to climb, and others almost too muddy or rocky to navigate. The bottom of our car crunches and scrapes as we creep along toward his village.

Eventually we reach the compound where Laith lives with his family. Laith’s house, the family’s olive trees, and two other houses belonging to his extended family are surrounded by a short rock wall topped with barbed wire. When we pull up in our car, a dozen or more kids come spilling out to greet us—Laith’s children and nieces and nephews. Some wear cracked plastic shoes, some wear no shoes at all.

Laith is a skinny thirty-two-year-old with a wife and five young kids. The seven of them sleep in a twelve-foot by twelve-foot room that includes a wardrobe, a crib for the baby, and twin bunk beds piled with blankets. This is the main room of the family’s living space. They also have a small kitchen and toilet, all of which is on the second floor, above a chicken coop.

After a tour of his house, we sit with Laith on plastic chairs outside, and he tells us about the ways his community has changed since 1996, when Israeli settlers first moved near his home. His wife stays close by, and even though she is hard of hearing, she interjects periodically with her own stories.

Laith is one of up to 300,000 Palestinians living in Area C—the roughly 60 percent of the West Bank that is still under full military and administrative control by Israel following the Oslo Peace Accords of 1993.1 Area C also contains many of the West Bank’s Israeli settlements, a collection of villages established by Israeli citizens following the occupation of the region in 1967. Today, there are 400,000–500,000 Israeli settlers in the West Bank outside of Jerusalem.

The guard tower of a nearby settlement looms above Laith’s property as we sit and talk. He tears up as he tells us that pressure from the settlements may force him to someday relocate his family.2

THE DAYS THAT HAVE PASSED ARE BETTER THAN THE DAYS THAT ARE NOW

I was born in Bethlehem in 1982, but I’ve lived here in my village southeast of Bethlehem for twenty-five years, since I was a little boy. My grandfather brought his whole family here from Bethlehem—my father and my uncle and their wives and kids. My extended family had land here going far back, and my grandfather inherited a piece of it. We have paperwork going back to 1943 that documents our right to these twelve acres and three houses.

The days that have passed, they are better than the days that are now. I remember how much fun it was as a child, taking care of my family’s farm and chasing animals in the wilderness nearby, and just living on the land. We went on picnics. It was nice. It was normal. We worked and moved easily with no restrictions. We were happy, with a simple life.

Then, when I was around fifteen years old, the settlers came onto our land. There had been settlements in the area since I was a boy, but none so close. First, we started seeing roads going in sometime around 1996. That same year, the first settlers showed up in trailer homes. There were maybe fifteen to twenty trailers that appeared near our village. These first settlers were just a few families. But they were never without guns—AK-47s, big guns. The first thing they did was come to the village to see if they would have any trouble. They were pretty rough. There were some clashes at first over land. I remember one old man whom the settlers struck on the head—he almost died. They also started building a fence around the settlement and some of our farmland right away. We had a fence around most of our property, and that helped keep the settlers from building directly on our land, but they took the land where our sheep graze outside the fence, about a thousand square feet of grazing land. They also took some of my father’s sheep. And they took other villagers’ land and sheep when they could.

At one point in 1996, the villagers had a big protest. We set up tents around the village, and there were about a hundred of us protesting the settlers taking our land. There were human rights groups at the protest, and we explained things to them. But it didn’t matter. The settlers just attacked us, struck us with their guns. After that protest and some early clashes with the settlers, the villagers here just gave up.

THEY SAID A BULLDOZER WAS COMING

In the summer of 1997, the Israeli military came to my family’s home and demolished our sheep pen. It was a Saturday evening, and sixty or seventy soldiers arrived in jeeps. They gathered up my family—I was with my parents, six brothers, and four sisters—and they told us to stay in a single room. We also saw them go to my uncles’ houses, which were on the same property. At first they were just securing the area, making sure nobody protested or made trouble.

They said a bulldozer was coming. My father tried to argue with them. He said that the sheep pen was the first floor of what would be a new home that he was building for some of his kids. He needed to build a new structure to house his growing family. But the soldiers told him to be quiet and stay in the room, and then they locked us in. We could see what was happening out the window, and we watched for an hour and a half while they drove the sheep out and knocked down the house. We cried. We had just built the barn the year before, all by hand. It had taken months of work and it was a big investment.

We knew the soldiers might come. We’d gotten a demolition order the year before, while we were still building the first floor of the new structure. It was on our land, but the Israeli authorities said we didn’t have a permit to build it. Many people in the village got similar notices that demolition was planned on houses or buildings they’d built without permission from Israel. But the Israeli military only demolished two buildings that day—our sheep pen and one other home in the village, the home of some neighbors half a mile away. I’m not sure why they chose our structure. Afterward, we had to take turns sleeping outside with the sheep, to protect them. We live near a wilderness, and there were wild dogs and jackals to worry about. After we cleared away the rubble, there were still a couple of the walls left, so we put up a tarp and that became the new sheep pen.

I remember the feeling I had after that day, a suffocating feeling. Our family was large, it was growing, and we weren’t allowed to build. My father wanted to grow the farm and build homes for his children, but he wasn’t allowed to. His plan had been to build upward, adding floors to existing structures. The sheep pen was a new structure, and he wanted to build more floors on top of it for his children to live in when they started families of their own. But after the demolition, that was no longer possible.

My family tried again a couple of years later. Around 2000, we bought stone to build a new house on the property. We paid about 60,000 shekels.3 This time, we tried to get a permit to build. There was so much we had to do, so many requests of us—money, negotiating with lawyers, endless paperwork. My father tried three times, but we couldn’t get a permit. The stones we bought to build a new house are still on the property today. It’s just a pile of marble that’s been sitting there for fourteen years.

Many people in the village have gone elsewhere. Some of my uncle’s family members who used to live on the property have gone to live abroad. The Israelis, the settlers, it seems like they want us to go away. If we didn’t have this land, we’d go back to Bethlehem. It’s a better place—it’s easier to live there. But if we leave, we won’t be able to protect the land, which has been in our family for generations.

WE ARE LIKE PRISONERS HERE

I got married a few years after the demolition on our sheep barn. I needed to find a job to make more money, since my wife and I wanted to start a family. So I found work at a marble company in a large settlement a couple of miles from here, and I worked there for three years. But work stopped and the workers were let go in 2008. Around this time my wife and I were growing our family. We had children, and we needed money. So I began entering Israel illegally to work. I snuck in once to do some work on a construction site. I tried to sneak in a second time, but I was caught by the army. They put me in jail for two months, and I couldn’t apply for a permit to work legally in Jerusalem for years.4

Since then I’ve worked around the family home. My family has sheep and goats, but I just take care of the chickens. I have about forty of them, and I get around ten eggs a day. The eggs we don’t eat we sell in the market. We also grow most of our own vegetables—cucumbers, cabbage, beans. And we have about three hundred olive trees on the property. We make about eighty gallons of olive oil every year, and we sell what we don’t use.

Most days during the week, I wake up at six-thirty in the morning and go to work by seven. Right now I’m working in the olive groves on the farm in the nearby settlement. It’s the time of the season when we dry the olives. I actually don’t like working in the sun—I get dizzy and I get headaches—so my job is to work inside where I help get the olives ready for packing. I usually work from seven to three, but sometimes I get overtime and stay until five. I’ve also done work in the nearby settlements preparing firewood, making bricks, doing other jobs. I talk to the boss, and he tells me where I should go to find work. In general, I like working in the settlements because I can travel back and forth easily, see my kids more. But the work I get around here doesn’t pay much. I get about 100 shekels a day, usually. My friends who go into Jerusalem, they get a little more—150 or 175 shekels.5 I used to go with them sometimes, but you need a special permit, and I haven’t been able to get one since I was arrested.