“It’s a long time ago. I don’t know where to begin. Plus…”

“What?”

“Man, by the time we made the recording, I was already high. That’s when I really started using, maybe right after that, and then there were some heavy-duty sessions, a high-level recording studio or some shit, but I swear, man, other than that, I do not remember one fucking thing.”

“But you remember that Reynaldo Durazo was killed.”

“Honestly? I know it in here—” He pointed a bony finger at his temple. “But that whole time is just one bad blur.” He popped the top off his strawberry shake and considered the cold pink foam. “Only thing I really remember is how unhappy I was.”

I said, “The papers wrote that Reynaldo was a drug dealer. Was he the one you were scoring from?”

Sandoz rolled his eyes as he shook out fries onto a bed of ketchup. “Rey-Rey was no drug dealer. Rey-Rey was just some dork we went to school with.”

Sandoz gave me a weak smile.

“Couldn’t keep a beat to save his life. He begged to be in the band, told us he had a kit. That was good enough for us. ‘You’re hired.’ ”

“But did he and Emil have some kind of beef?”

“No way. Elkaim was Mister Mellow. I never saw him have beefs with anyone, ever. He wouldn’t have punched Rey, let alone kill him. Emil was kind of, not our leader exactly, but he was the courageous one. We ran through a lot of guitarists before he showed up, but once we heard him play, it was over, man; he was the heart and soul of the band.”

“So what the hell happened?”

Sandoz whispered, “I don’t know, man.”

He ate his Double Chili in a kind of meditative stupor, but he was slowly coming back to life. The right burger could do that to an Angeleno. I watched him and wondered what he was remembering, or trying to remember.

I said, “Is it true you had a thing with Marjorie Persky?”

“Who?”

I raised eyebrows.

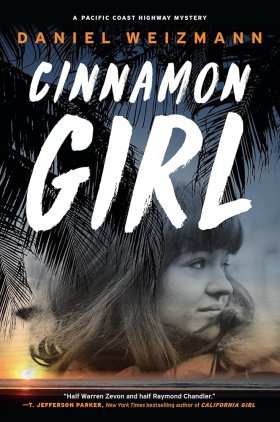

“I knew Cinnamon Persky—you mean her mother?”

“Yeah,” I said, “that’s who I mean.”

“I didn’t know her.”

“What about after the band. You served,” I said, pointing at the tags.

“Yeah. Wrong decision number five hundred fifty-two.”

“So why’d you do it?”

“After all the shit went down, losing Rey and Emil, I quit high school, I tried to sober up. Then I enlisted. I was totally lost. I didn’t think there was gonna be a real war. All of a sudden, Desert Storm, I’m stationed in Mina al Ahmadi, driving a T-72—the skinny rock dude who never should have been sent into combat.”

He laughed, but under the goof, the permanent wound to his safety vibed through.

“A long way from The Daily Telegraph,” I said.

“After what happened, there was no Daily Telegraph.”

“I got your LP.”

He groaned. “I haven’t heard that piece of shit in years.”

“But it’s great.”

“Come on, man—we maybe did five gigs. We stunk. Never shoulda left the garage, what fucking hubris.” Despite the words, talk of the band lit him up even more—the death glow fell off like dried lizard skin. He reached for his strawberry milkshake. “If we made it to the end of a song, it was like a minor miracle.”

“And you and Hawley stayed close?”

“I wouldn’t call it that. I tried to stay close. He just, like, tolerated me.”

“I don’t get it.”

“You know, man, when a band breaks up, it’s like a divorce. Hawley got insular, cut everyone off. He didn’t want to jam, hang out, nothing—total blackout. I lost my whole world in, like, three days.” Sandoz breathed deep, eyes fragile. “You really found him?”

I nodded. The night air around us seemed heavy, thick with exhaust. Sandoz looked at the last of his food but didn’t eat. Mourning was creeping back up on him. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a pint of Classic Club gin, emptied it into his milkshake. Then, from his other pocket, he fished out a prescription bottle—he shook out two pills, then a third, gobbled them and slugged the loaded shake.

Then he said, “Dev was what people now call obsessive compulsive. But we didn’t have a name for it.”

“What makes you say so?”

“Oh, he was fixated, totally. He could not let go of the past.”

“That’s what Grunes said about you.”