“Yeah, well, fuck that guy—Methinks he doth protest too much. I reminisce but Devon was doing shit. He was even in touch with Durazo’s cousin, hounding her night and day.”

“So he was actually trying to find out who killed Durazo, like, this whole time?”

“Yup. He had this big, like, wall collage, filled with what he called leads—I saw it. It looked like a lot of BS to me. Recently, he even hired this pro detective, but the guy only got so far.”

“I heard the guy flopped and gave up.”

“Bullshit—he didn’t give up; he quit. And Hawley freaked. He was real upset about it last time I talked to him. He was all, like, ‘It doesn’t make sense; it doesn’t make sense!’ I think Dev thought the guy got bought off or something.”

“By who?”

Sandoz shrugged.

“Did Hawley tell you the detective’s name?”

“Gladstone. Martin Gladstone—when he quit, Dev practically had a nervous breakdown.” Long pause—Sandoz stared out at the gasoline vapor. “Like finding out who really killed Rey would change anything.”

“Wouldn’t it?”

“No. Absolutely not. It’s done, man. Our youth is gone—into the black hole.”

Energized, Sandoz got restless, held hostage here at the fast-food shack, trapped between the scratched-up blue-green bench and tabletop. To blast free, he poured more gin, took another pill, and started lecturing me. First about his bad marriage and the treachery of living under his father’s thumb. Then he digressed on why being in a band is for people who need a real family. But then he monologued himself into an anti-rock tear. In twenty years, he had not placed a single rock track on his Pandora, not classic rock, punk, alt, or otherwise; he hated all of it. He was a karaoke crooner now, a jazz convert, but he didn’t seem that happy about it. Then he started thrashing the internet, a familiar riff. He said that hard drugs were healthier than Facebook. Pointing ketchupy fries at me, he insisted we were on the precipice of complete cultural dissolution, which didn’t stop him from loving Rick’s Charbroiled. Then when he finished eating, he tossed his wrappers in the trash and returned to the table to tear Grunes and the LAUSD a new one. Sandoz wasn’t homeless by default; he insisted he chose it. He only felt at home with crazies, bangers, and the permanently wayward.

“I’ve come to know a thing or two about human personality,” he said, “especially teenagers. Now I see—I should have guessed what was going to go down with our band all along.”

“Really? What were the signs?”

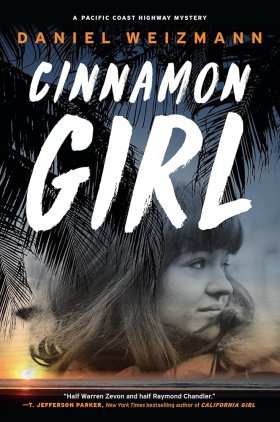

“Cinnamon was on fire. She was looking for trouble; it surrounded her. She was way ambitious. And she was fast.”

“Because of Emil?”

“No, no, the opposite. Elk had to race to keep up with her. She was out on the Strip every night, hanging at the Whisky, the Roxy, handing out acid, these great big sheets of perforated tax stamps she kept rolled up in her purse. And she always had some coke on her, too. I won’t say she was a groupie, but she was some kind of ambassador to all the British bands that came through, Tin Tin Duffy and all that eyeliner bullshit.”

“What was her role in The Daily Telegraph?”

“Her role? Well, she was kind of our de facto manager. She had big plans for us. Actually, I didn’t know how in-crowd Cinnamon was till I bumped into her at one of the Mind-Life Potential seminars.”

“Mind-Life Potential?”

“Yup, it was a thing in the eighties.” Sandoz put on the anchorman voice. “Harness the power of aggressive positivity through Mind-Life Potential.”

“You did the seminar?”

“Yeah, we all did. It was supposed to make you more self-aware, more confident, all that bullshit—they had all us high school kids walking around like zombies, spreading the gospel. Somebody in the A/V club hustled me, and I signed up. I was a high school nerd with bad acne, ya know? I craved me some major guidance.”

“What about your parents?”

“My family scene wasn’t too cool. My dad was a fireman; he only slept at home, like, one in three nights. My mom was morbidly obese. She couldn’t hardly get off her ass to change the TV channel. Of course, today I understand she was depressive, but back then, like I said, we didn’t have the right words. Man, I’d go anywhere after school instead of going home.”

“So, Cinnamon showed up at this thing, too?”

“I thought she was the squarest girl in school. A preppy.”

He said the word with true contempt.

“You know, a drill squad girl in purple Lacoste and overpriced sneakers. But no, she shows up, and lo and behold, she’s the It Girl, knows everybody. She was dressed different than at school, too. She wore this super-short miniskirt and all kinds of bangles and stuff; all the dudes were drooling over her, including me. At the seminar, I didn’t dare speak to her. But afterward, I got the courage to offer her a ride home. I had this killer Vespa P200E that I bought with money I earned being a movie usher. Cin very politely turns me down. And then…”

He took a slug from his shake, impatient with himself.

“This is what really blew my mind. Just as I’m revving my scooter, up drives these two slick older dudes in this convertible red whatever, probably a Mustang or a Camaro or something. And they are there expressly to pick up Lady Cinnamon. I froze in my tracks. And that’s when I realized who these guys were—they were famous DJs, these two bigtimers. I’d seen their faces on billboards, man. I stood there like an idiot and watched the three of ’em drive away and, I’ll never forget this, Cinnamon turns back and waves goodbye to me and she says, ‘See you in homeroom, Mickey.’ Just like that—whoosh!—they’re off to the races. Here I was, thinking I was the cool cat on campus, and this ultra-square girl is being chaperoned by, you know, icons.”

“You saying she went out with one of them or—”

“Those two hound dogs? You’d have to ask them. If they’re still alive. They’ve been off the air since forever, but the thing was, back then, they had the most popular oldies show on K-Earth. They were, like, city heroes. And they had this thing—Can YOU Spot the K-R-T-H DJs? Catch ’em if you can! You’d call in and if you could correctly identify the whereabouts of these assholes and the car they were driving, you’d win a trip to Disneyland or Knott’s or whatever. So you see, I had a dilemma. I could hit the nearest pay phone and say I had just spotted these guys, but then they’d announce the winner by name and Cinnamon would know it was me and…it just didn’t seem like the thing to do. So I didn’t. Next day, she leans over to me in homeroom, talking to me at school for the first time ever. And she goes, ‘Did you cash in?’ And I said something sarcastic like, ‘Do I look like I want to join the Mickey Mouse Club?’ and she just raised a very approving eyebrow and that was that. It was nothing, two tiny little events. But it changed me forever.”

“So, two old DJs gave her a ride somewhere,” I said. “I don’t get it, what’s the big deal?”

He sucked the last of his shake through the pink paper straw like a man taking his last drag before execution, but the color had returned to his cheeks once and for all and he was buzzing. It was like he’d morphed into his former heart-hurt kinetic teenage self, complete with odd-tilted posture. “Well, it was a big deal. Because…because I realized right then and there…I saw…”

He blushed.

“What, tell me.”

“Because it made me realize that there really was no such thing as cool. This thing I’d been trying to be since the age of ten, it didn’t exist. There was only one real law and that law was sex power. Period. Sex power. The world…was just a game of…sexual checkers, jump and capture—the only law. It overrode everything. Still does. And it was a shock to me, man. With my two parents flyin’ off each other like magnetic Scottie dogs, I never thought of sex that way—as a power. My dumb ass, I really thought sex was Can you get the pretty girl to love you? But when Cinnamon Persky hopped in the ride with those old dudes, I saw the light, right then and there. And it seemed so cruel. Sex power.”

He chewed his straw with ferocious concentration. Then he said, “Much later I heard she brought our demos to them, the DJs, but they didn’t do jack shit for us. Soon after, everything went to hell—but I never forgot that afternoon, all my life. Couple years later, I was stationed in Khafji and I thought I was gonna die; we were down in a desert bunker and they were rocketing the shit out of us, hot metal flying everywhere, and you know what? I remembered that moment, the feeling, seeing Cinnamon ride away, how it stung me. Actually, you know what? It made me less afraid of death.”

We sat, not speaking, listening to the sound of traffic around us, the car radios and horns and the drive-through intercom crackling through mixed-up orders. We were stranded, stranded on Cheeseburger Island.